Sergey Kurginyan and the Aleksandrovskoye commune present a new, revised edition of the collective monograph

Part I. Ukrainism: Historical, political and religious context and Part II. Ukrainism: Relevant international game

In 2014, outright neo-Banderites came to power in Kiev. People in Odessa who opposed the neo-fascist coup were burnt alive in the House of Trade Unions. For eight years, the Kiev regime bombed cities and towns in Donbass. The West was continuously preparing Ukraine for the war against Russia under the deceitful – as former German Chancellor Angela Merkel and former French President François Hollande openly admitted recently – cover of the Minsk agreements. And when Russia was forced to launch its special operation – neo-Banderite Ukraine was granted full-scale military and political support. What is the Ukrainian neo-Nazi entity, and where are its origins? And why is it receiving such powerful support?

Let us discuss the artificial construct called “Ukrainism” being created over the centuries.

In the 11th century, the united Ancient Rus’ arose. It was founded by the Rurikovich dynasty, who came from Novgorod. The center of this state first became Kiev, then Vladimir, and then Moscow.

In the 13th century, Russian lands were weakened by the Tatar-Mongol invasion.

Prince Daniel of Galicia, who ruled at that time in the Western Russian lands, has become the favorite hero of those who support the European way of Ukraine’s development. Unlike his contemporary Alexander Nevsky, Daniel concluded a treaty with Rome while seeking assistance against the Tatars and was crowned “King of the Rus” (Rex Russiae) by the Roman Pope. This, however, did not help Daniel to repel the invading Tatars. And his successors, princes of the principality of Galicia-Volyn, were subjugated first by Lithuania in the 14th century and later by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In 1596 Rome managed to impose the Brest Union on the Orthodox of the Western Russian lands, which fell under the power of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

The initiators of this union were several hierarchs. They were freshly installed by Patriarch Jeremias II of Constantinople, who was passing through these lands. The first supporter of the union, the newly installed Metropolitan Michail Ragoza of Kiev, was known for his submissiveness. The second one, Bishop Hipacy Pociej of Vladimir-Volynsk and Brest, was a secular person shortly before. He was ordained as a priest by the third, most active supporter of the Brest Union – Bishop Kirill Terletskiy of Lutsk and Ostrog. The court of Lutsk brought several cases against Terletskiy on charges of robbery, physical injuries, rape, and murder. Thus, one of the cases was initiated on the complaint of Adam Zakrevski, who reported that while passing through the bishop’s estate, he was attacked by church hierarch Kirill, “Late at night, when everyone was already asleep, the Bishop of Lutsk, His Eminence Kirill, suddenly appeared here… He began to scold Zakrevski, taking a bag with money, a horse, a carriage, and property from him and ordering to send it all to his estate. He also took with him maid Palazhka (a seamstress who accompanied Zakrevski), brought her to his house and raped her after locking himself with her in a chamber.”

These were the hierarchs who promoted the union. They personally asked the Apostolic See for it and, hastily leaving for Rome, swore an oath to the Pope.

The Orthodox population sharply opposed the union, but had to submit. By the beginning of the 20th century, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church established by this union finally became an obedient instrument of papal policy.

During a series of wars with Poland in the 17-18th centuries, Russian tsars gradually freed most of the Western Russian territories from rule by the Poles.

In the late 18th century, the partitions of Poland, which had been constantly fighting with its neighbors, took place. Russia received a part of its ancient lands. But the Galician lands were arbitrarily given to Austria. As noted by historian V. O. Kliuchevsky, “they say that during the first partition, Catherine [II] cried because of this concession; 21 years later, during the second partition, she calmly said that ‘after a while, it is necessary to negotiate with the [Austrian] Emperor about the exchange of Galicia, it does not suit him’; however, Galicia remained under Austria even after the third partition.”

The Austrians united the Galician lands with the Lesser Poland they had obtained and put them under the rule of the Poles.

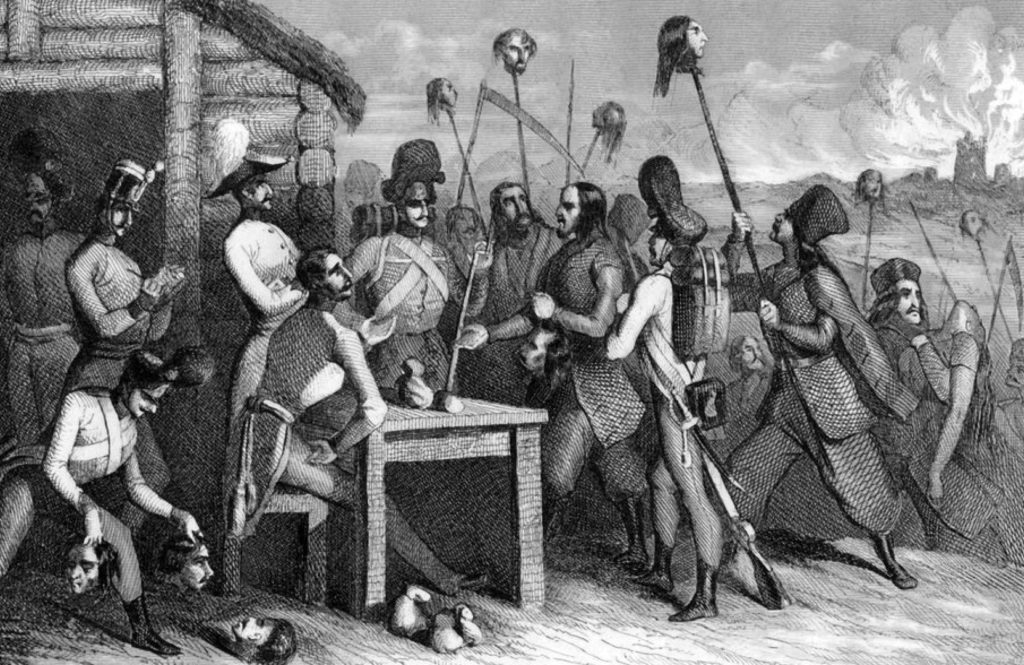

In the mid-19th century, the Austrian authorities began to fear the strengthening of the Poles and a sharp increase in their protest sentiments. In 1846, the Austrians pitted the peasants of Galicia against the Polish nobility. Agents of Vienna spread rumors about reprisals against the peasants allegedly planned by the Polish nobles and about the temporary “abolition” of the Ten Commandments by the Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I. The Austrians paid for the heads of the murdered Polish nobility. The epicenter of the brutal massacre was Western Galicia, whose inhabitants were overwhelmingly Mazurians, i.e. Polish peasants. Nevertheless, many researchers believe those events became a cause of the “gene of violence” also introduced in Eastern Galicia, i.e. in the Western Ukrainian lands. The son of the then police chief of Galicia Leopold von Sacher-Masoch, the first documented case of the masochism phenomenon, witnessed the massacre as a child. In his novel A Galician Story 1846 [German: Graf Donski. Eine galizische Geschichte. 1846] Sacher-Masoch described peasants slaughtering Polish nobles with scythes. The novel abounds with such pictures, “Shoot, shoot!” shouted Korski; but before he managed to pull out his ponderous pistols, the blows of scythes and chains rained down on him.” Contemporary researcher Larry Wolff points out that the “Galicia Slaughter” had a traumatic effect not only on Sacher-Masoch in his childhood, but on the whole Galicia, “… there was, in fact, a Galician substratum that conditioned Sacher-Masoch’s personal and literary anomalies. The years of his Galician childhood from 1836 to 1848 were formative and traumatic not only for him but also for the historical course of Galicia itself.”

Let us recall the recent sensational staged video showing a Ukrainian woman in a vyshyvanka eagerly cutting the head of a Russian soldier in a telnyashka undershirt off with a sickle. This Ukrainian woman with a sickle was turned into a symbol of contemporary Ukraine. Those who shot this video were obviously awakening the collective historical memory, impairing the consciousness, and encouraging Ukrainians to commit atrocities against the defenseless. And atrocities against Russian prisoners of war followed… As we have seen, in the 21st century, the Ten Commandments are once again abolished for Ukrainian minions – but today, the clown Zelensky is playing the role of Emperor Ferdinand.

The “Galicia Slaughter” alienated many in Galicia from the Austrians and strengthened the already existing Russophile sentiment. The Austrian authorities, fearing the orientation of the inhabitants of these lands towards Moscow, tried to force them to change their self-identification. This also included the replacement of the self-designation “Rusyns” by the Austrian “Ruthenians”.

Later, the leader of the Russophile movement Father Ivan Naumovich recalled the visit of Rusyn representatives in April 1848 to the Governor of Galicia Franz Stadion, “In 1848 they asked us, ‘Who are you?’. We said that we are the most humble Ruthenen. (My God, if our forefathers had known that we called ourselves by that name, which our greatest enemies gave us during the persecution, they’d turn in their graves!) <…> We swore with our souls and bodies that we are not Russians, not Russen, but that we are just Ruthenen, that our border is on the Zbruch, that we shun the so-called Russen, as vicious schismatics, with whom we have nothing to do.”

The Poles soon began to work actively on the Ruthenian question. The Polish emigration – the so-called Hôtel Lambert of Prince Adam Czartoryski and its representatives such as Franciszek Duchiński and Michał Czajkowski – developed the myth of the Cossacks-Ukrainians as “true Russians”, which they opposed to the Asian Moscow. The racial research of the Pole Duchiński stated that the Moscals were neither Russians nor Europeans but “Turans” and that they were a different, Asian race altogether.

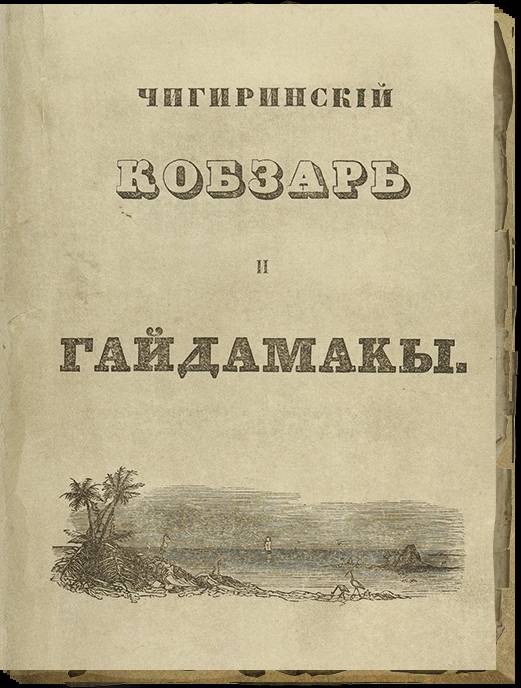

Representatives of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood in Kiev, including Taras Shevchenko, had close ties with this Polish emigration. Shevchenko, for example, imitated Czajkowski’s Wernyhora in his Gaidamaki poem about the Cossack uprising in 1768. Shevchenko’s publisher Pyotr Ivanovich Martos recalled, “I came across Czajkowski’s novel Wernyhora in Polish, published in Paris. I gave Shevchenko this novel to read; the content of ‘Gaidamaki’ and most details are entirely taken from there.” Czajkowski also added to his novel the lie that Catherine II was allegedly to blame for the uprising and other fabrications. Books of the Genesis of the Ukrainian People, considered in contemporary Ukraine as a manifesto of Ukrainian messianism, is actually a copy of The Books of the Polish People and of the Polish Pilgrimage [Polish: Księgi narodu polskiego i pielgrzymstwa polskiego] by the Polish poet Adam Mickiewicz.

Stanisław Tarnowski, a Polish figure closely connected with the Hôtel Lambert, directly pointed out that Russian Ukrainians should be attracted to Galicia and Poland, “Here, in Galicia, we should not exterminate, but nurture and cultivate the Rusyn nationality, and it will be consolidated over the Dnepr. Here, in Lvov, we should let it develop, and soon it will draw into itself the juices of Volyn, Podolia and Ukraine. <…> It will be a Rus’, but a Rus’, which is fraternal to Poland and together with it devoted to one cause.”

The Austrians also actively encouraged Ukrainism, seeking to separate the Russian Ukraine – Little Russia (Malorossyia) – from Russia and unite it with Austrian Galicia.

In 1894, the Austrians officially invited the Ukrainophile Mikhail Grushevskiy from Kiev to spread Ukrainism in Galicia. He was appointed professor of history at Lvov University. In his articles and from the university chair, Grushevskiy preached about an ancient “Ukraine-Rus” and “Ukrainians-Rusyns”, speaking in a language that he called “Ukrainian”. Having created his own version of the “history of Ukraine”, Grushevskiy also deliberately introduced an abundance of Galicianisms and Polonisms into the “Mova” [Ukrainian language] he used. They have remained firmly entrenched in the Ukrainian language ever since.

On the eve of World War I, the Austrians planned to occupy Little Russia and unite it with Galicia. Vienna also had its own candidate from the Habsburg dynasty for the Ukrainian throne – Wilhelm von Habsburg-Lothringen, who dreamed of ruling the Grand Duchy of Ukraine.

The plan for annexing Russian Malorossiya to Galicia was formulated immediately after the outbreak of the war, on August 15, 1914, in a note to the Austrian Ministry of Foreign Affairs by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptitskiy, who had close ties with the Ukrainian nationalists. The note suggested, “As soon as a victorious Austrian army enters the territory of the Russian Ukraine, we will have to solve a threefold task of the military, the social-legal and the ecclesiastical organization of the country: […] to separate these areas as radically as possible from Russia at every opportunity, in order to stamp on them the character of a national area independent of Russia and alien to the Tsarist Empire, which is congenial to the population.”

But already on August 31, 1914, Baron Wladimir Giesl von Gieslingen, representative of the Austrian Foreign Ministry at the Army Headquarters, reported to the Foreign Ministry after negotiations with the leaders of Ukrainian organizations in Lvov, “The Ukrainophile movement has no support among the population – there are only leaders without parties.”

After the Russian army entered the territory of Galicia, Giesl informed the Austrian leadership about the mass defection of Rusyns to the Russian side.

The Austrian Supreme Commander Archduke Friedrich wrote in a report to Emperor Franz Joseph I that the Rusyns perceived the Russian troops as liberators and that the Russians could “count on the full support” of the local population.

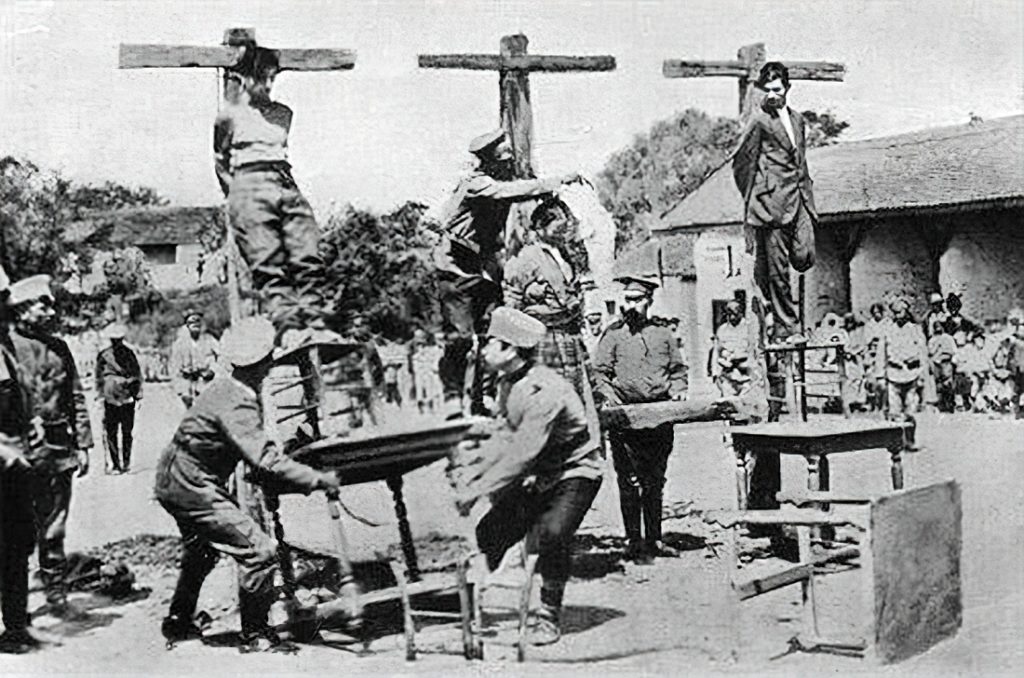

During the war, the Rusyns were brutally persecuted by the Austrian authorities for supporting the Russians, resulting in almost all Russophile intellectuals and many thousands of peasants being exterminated. The Rusyns were arrested according to lists their Ukrainian neighbors prepared in advance and kindly provided to the Austrian authorities.

Against the backdrop of the Russian offensive in Galicia in August 1914, local massacres took place. “In retaliation for their failures on the Russian front, the fleeing Austrian troops killed and hanged thousands of Russian Galician peasants in the villages. Austrian soldiers carry in their kit bags ready-made nooses and wherever they can, on trees, in peasant houses, in barns, they hang peasants who identify themselves as Russians and are therefore reported by Ukrainophiles [to the Austrians] … Galician Rus’ turned into a gigantic terrible Golgotha…” composer Elias I. Tziorogh later recalled during his exile in the United States.

The surviving Rusyns were thrown to perish in concentration camps, the most terrible of which were Talerhof and Terezin. The prisoners were treated like cattle – they died from epidemics, they were brutally tortured and killed for the slightest offense. “Talerhof had once and for all become the name of the German hell. <…> Until the winter of 1915, there were no barracks in Talerhof. People lay on the ground in the open air in the rain and frost. <…> Mud was the best soil and abundant food for innumerable insects. <…> Priest Ioann Mashchak under the date of December 11, 1914 noted that 11 people were just gnawed by lice,” the writer Vasiliy Vavrik recalled, who was himself a prisoner of Talerhof.

In the Russian Empire, Ukrainian nationalists were preparing secession in advance. Immediately after the October Revolution, the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) declared its independence.

In 1918, under the terms of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (the so-called “Bread Peace”) between the UPR and Central Powers, the Austrians and Germans promised military aid to the UPR. In return, the Ukrainians were to supply one million tons of grain, as well as meat, eggs and so on. The Germans and Austrians promised to give the UPR the captured Russian Kholmshchina, while the Austrians also pledged to grant autonomy to Eastern Galicia, which the Rusyns had long sought. But these agreements were not fulfilled under the pretext that the UPR did not deliver the required amount of grain in time.Austria-Hungary would soon collapse under the pressure of internal ethnic problems.

The Germans arranged a coup in the UPR and installed their protégé Hetman Skoropadsky there. The UPR under Skoropadsky became a puppet German state. In the frank words of the German ambassador to Kiev Philipp Alfons Mumm, the Germans had to support “the fiction of an i n d e p e n d e n t state friendly to us” with regard to Ukraine, which was entirely dependent on the Germans.

After the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the short-lived West Ukrainian People’s Republic (WUPR) emerged in the West Ukrainian lands. In 1919, the UPR and WUPR even managed to unite. But soon after, all these quasi-state entities disappeared from the world map.

In the territories of Galicia and Western Volyn, ceded to Poland, Ukrainian terrorist structures – the Ukrainian Military Organization (UMO) created by former UPR officers and its successor, the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists* (OUN)* – became active. Since the 1920s, Ukrainian terrorists had ties with the Germans, who hoped to use them in the fight against the Poles.

In Poland, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church actively assisted Ukrainian nationalists.

For example, Andrey Melnik, a UMO member and one of the future OUN* leaders, worked as a forestry administrator for the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church after his release from prison in 1928.

The metropolitan forestry department was located in the territory of Metropolitan Sheptitskiy’s summer residence in Gorgany. This territory was also used to hold meetings of the Ukrainian nationalist youth organization Plast. The grateful Plast members even awarded a “swastika of gratitude” to the Metropolitan.

Sheptitskiy appointed a special clergyman to assist the nationalists imprisoned in Poland. This clergyman Josef Kladotschny actually acted as a liaison. His enthusiasm knew no bounds when Kladotschny later recalled the leader of the Ukrainian nationalists Stepan Bandera, “He radiated willpower and determination to get his way. If there is an Übermensch (Superman), he was indeed of that rare breed of supermen, and he was the one who put Ukraine above all.”

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church founded a Christian nationalist movement that actively engaged young people. Thousands of Galicians belonged to the Catholic associations. The priests in charge of such associations made all possible efforts to implant an ultranationalist ideology in the West Ukrainian residents under the guise of Christian nationalism.

The student organization Obnova [English: Renewal] was active in Galicia since 1930. The students of Lvov Theological Seminary and the Faculty of Theology of Lvov University formed its core. In the same year, Sheptitskiy invited Nikolay Konrad to teach at Lvov Theological Academy, who became the head of Obnova.

In his article “Nationalism and Catholicism,” Konrad wrote, “The contemporary Catholic and nationalist movement is a new crusade of Catholicism with the slogan: I Believe! This is what God wants! and nationalism with the slogan: I want! Voglio!.. The sword and the cross are the hope of nations and humanity for a new and better tomorrow, so that pax Christi in regno Christi may reign.” Konrad tried to convince the reader of Hitler’s, Mussolini’s and Goebbels’ desire to defend Catholicism and expressed the fervent hope that, following the example of Germany and Italy, religion and nationalism would harmoniously unite as “two pure tones of the Ukrainian soul in one chord.”

After the Nazis came to power in Germany, the Ukrainian nationalists’ ties with the Germans became even closer. It was planned that the Ukrainian uprising would be timed to coincide with the German occupation of Poland.

However, Germany concluded a treaty with the USSR in 1939, according to which Western Ukraine was included in the Soviet zone.

After establishing Soviet power in Western Ukraine, the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church had to conceal its activities in Western Ukraine. Sheptitskiy’s disciple Josef Slipy wrote his “Main Rules for Contemporary Pastoral Ministry” in 1940. It was a detailed guide on lying and getting along with the authorities. Just one example, “A priest is threatened that he will be sent to exile if his daughter does not join the Komsomol. The girl agrees to join. In class, the teacher asks her if she knows that it is forbidden to perform religious rituals. She gives a vague answer, ‘I know what kind of obligation I’m making’.”

Meanwhile, the Nazis continued to plan their “Drang nach Osten” [English: “Drive to the East”] and were actively establishing relations with the OUN*-members on the eve of the war.

In February 1941, an agreement was reached between the chief of the Abwehr Admiral Canaris and Bandera on training 800 Ukrainian fighters by the Wehrmacht.

Alfred Rosenberg, head of the NSDAP Office of Foreign Affairs, was particularly zealous among the high-ranking Nazi leaders in advocating the fight against the Russians with the help of national minorities. On April 2, 1941, he presented a note to Hitler proposing that the territory of the Soviet Union be divided into seven regions. In Rosenberg’s concept, Russia was represented by the historical Russian center – Muscovy – and the ethnically foreign territories it had acquired over the centuries. About Ukraine, Rosenberg wrote, “Political goals in this territory might be the support for national identity, possibly to the degree of founding sovereign states, which could exercise the permanent containment of Moscow and provide security from the East for greater German living space, either as standalone or in cooperation with Don and Caucasus within The B l a c k S e a Alliance.”

Hitler did not like the idea of a sovereign Ukrainian state. And a few days later, Rosenberg submitted another memorandum, in which he used more vague terms to propose the creation of a Ukrainian state “which will be in close, inseparable union with the German Reich.”

The “Drang nach Osten” doctrine has its roots in the research field “Ostforschung” [English: Research on the East], which emerged in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. Numerous institutes were active in this scientific field.

The Institute for East European Studies in Breslau [now Wrocław in Poland], headed by NSDAP member Hans Koch, played an important role in this network. Koch served in the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, headed by Rosenberg. Precisely Koch helped to establish contacts with the OUN*-members before the war.

Another Ostforschung expert was Theodor Oberländer. Together with other authors, he developed the concept that called for the resettlement and extermination of the population of Eastern Europe for the purpose of Germanization. Oberländer advocated the extermination of Jews in Poland and the subjugation of Poles and became known for his statement about “eight million overpopulation” in Poland.

The Ukrainian Scientific Institute in Berlin, headed by Ivan Mirchuk, conducted its activities under the auspices of German governmental institutions. Vyacheslav Lipinskiy, a close ally of Hetman Skoropadsky and author of the pro-fascist concept of “classocracy,” was employed by this institution. Lipinskiy’s concept asserted the existence of an “active race” of masters and a “passive race” of slaves. Lipinskiy proposed establishing a “classocratic monarchy” in Ukraine relying on the “knight”-Cossacks, i.e. the hetmanate. Vladimir Kubiyovich, a geographer, worked at the same institute. Professor Zenon Kuzelya, who, according to Soviet intelligence reports, was in contact with Rosenberg’s office, was also employed there. On the eve of the war, the institute published German-Ukrainian dictionaries for various army forces, maps, etc.

Under the agreement with the Germans, the OUN*-members underwent training in early 1941 in Abwehr secret schools for participation in the war against the USSR. Ukrainian nationalists were formed into battalions Nachtigall and Roland (also known as the Legions of Ukrainian Nationalists) under the Abwehr’s special forces unit Brandenburg-800. Oberländer became Nachtigall’s liaison officer to the Abwehr. The Ukrainian commander of the battalion was the nationalist Roman Shukhevich.

After the Nachtigall battalion marched into Lvov with the German troops in 1941, the massacre of Jews, Poles, and communists began there.

Immediately after the arrival of the Germans, the Banderite Yaroslav Stetsko proclaimed the “Ukrainian state” in Lvov. This is how the Ukrainian nationalist Kost Pankivskiy, who was a member of the elected government, described the event, “Around noon, the OUN* leaders in civvies arrived in Lvov: Yaroslav Stetsko, Yevgen Vretsion, Yaroslav Starukhinsky and others. They arrived in Wehrmacht vehicles and, having contacted their men in the city, began to call a public meeting for the evening in the house of the Prosvita society. <…> Father Grinyokh, who appeared in the uniform of a German officer, made a speech after Stetsko and spoke vividly and temperamentally. He greeted the meeting on behalf of the legion’s commander and his soldiers. <…> No one from the local Lvov society spoke because no one was invited and no one asked for this. Only the rector Father Slipy welcomed the meeting on behalf of the Metropolitan.”

The next day Metropolitan Sheptitskiy’s address to the Ukrainian people was released, which read, “We welcome the victorious German Army as a liberator from the enemy. We render due obedience to the established authority. We recognize Mr. Yaroslav Stetsko as the Head of the Regional Government of the Western Regions of Ukraine.”

Hitler did not like the excessively independent actions of the OUN*-members. The Ukrainian state was abolished. The Banderites leaders were put in a concentration camp but in quite comfortable conditions. At the war’s end, the Germans would release and support them.

Entirely collaborationist political structures were being created in Ukraine, which suited the German authorities quite well.

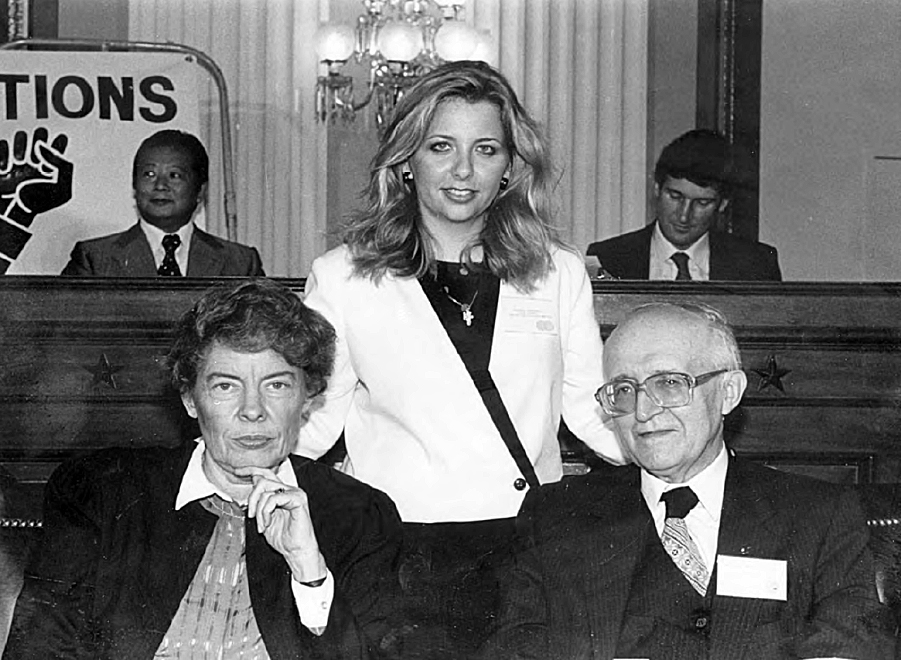

The Ukrainian Central Committee, with its headquarters in Krakow, was the most collaborationist. It was headed by Vladimir Kubiyovich, who worked at Mirchuk’s Ukrainian Scientific Institute in Berlin before the war. Metropolitan Sheptitskiy supported the creation of this committee. The Ukrainian Central Committee, in particular, oversaw the work of the Ukrainske Vydavnytstvo (Krakow) [English: Ukrainian Publishing House], to which the thoroughly anti-Semitic newspaper Krakivs’ki visti [English: Krakov News] belonged. Its editor was Mikhail Chomiak, the grandfather of the current Canadian Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland.

Ukrainian militants from the battalions Nachtigall and Roland committed brutal war crimes first in Ukraine and later in Belarus as part of the Schutzmannschaft [auxiliary police] Battalion 201.

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church actively supported all collaborationist structures.

Yevgeniy Pobegushchiy, who first commanded the nationalist Roland battalion and then the Waffen SS Division Galicia* regiment, visited Sheptitskiy and received blessings from him. “We must, yes, we must train and create our units at every opportunity and everywhere,” the Metropolitan said, according to Pobegushchiy, when he approved the creation of the nationalist battalions Roland and Nachtigall under the Abwehr. He later said the same thing to Pobegushchiy about the SS division Galicia*. Pobegushchiy was in constant contact with Sheptitskiy. In a letter dated May 19, 1942, he informed the Metropolitan, “We, your children, are all well and fulfilling our duties – the eradication of Bolshevism.” At the end of the same year, he wrote, “I sincerely thank you for the heartfelt words with which you have gifted us and strengthened us for the struggle against the Bolsheviks.”

In 1943, the initiator of the SS Division Galicia* Vladimir Kubiyovych received approval for its formation from Sheptitskiy. Kubiyovich recalled how he spoke “with the highest authority for Ukrainians – Metropolitan Andrey, and heard from his mouth, ‘There is hardly a price that should not be paid for the creation of the Ukrainian army.’”

Among the volunteers of the newly formed division were many who had previously participated in war crimes while serving in the nationalist battalion Nachtigall and the Schutzmannschaft Battalion 201. Units of the SS Division Galicia* itself participated in punitive actions against civilians in Western Ukraine, Poland, and Slovakia.

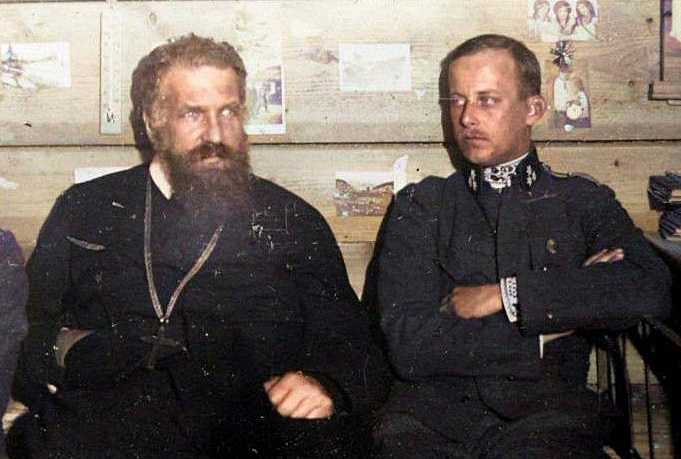

![Schutzmannschaft [auxiliary police] Battalion 201 (Roman Shukhevich in the foreground)](https://eu.eot.su/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/5f5b34a33a8b.jpg)

At the war’s end, in 1944, Rosenberg and some senior SS officers put forward a project to create a Ukrainian National Committee. Rosenberg proposed Skoropadsky as its head and tried to negotiate indirectly with Bandera and Melnik. However, the Ukrainian nationalists could not reach an agreement at that time.

Instead, the Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia under the chairmanship of Vlasov was formed with Himmler’s support. Rosenberg reacted very irritably to this and wrote in his diary, “First acceptance of my concept as of April 1941: to enlist all nations, especially the Ukrainians. <…> After activation by RFSS. [Reichsführer SS], they give a green light to Vlasov. <…> W. [Vlassov] will now write the sacrifices of the others in the Russian account book.”

In 1945, the Ukrainian National Committee (UNC) was nevertheless established at Rosenberg’s suggestion. General Pavel Shandruk was appointed its head, while Kubiyovich became Shandruk’s deputy. The SS Division Galicia* was transformed into the First Division of the Ukrainian National Army under the UNC. This was later used to allege that neither the division nor the UNC were collaborationist structures.

After the war, former Nazis were secretly brought to the United States, Canada, and Latin America as part of Operations Paperclip and Ratlines. They were very quickly integrated into the Western states’ political and military structures, which actively employed them to fight against the USSR during the Cold War.

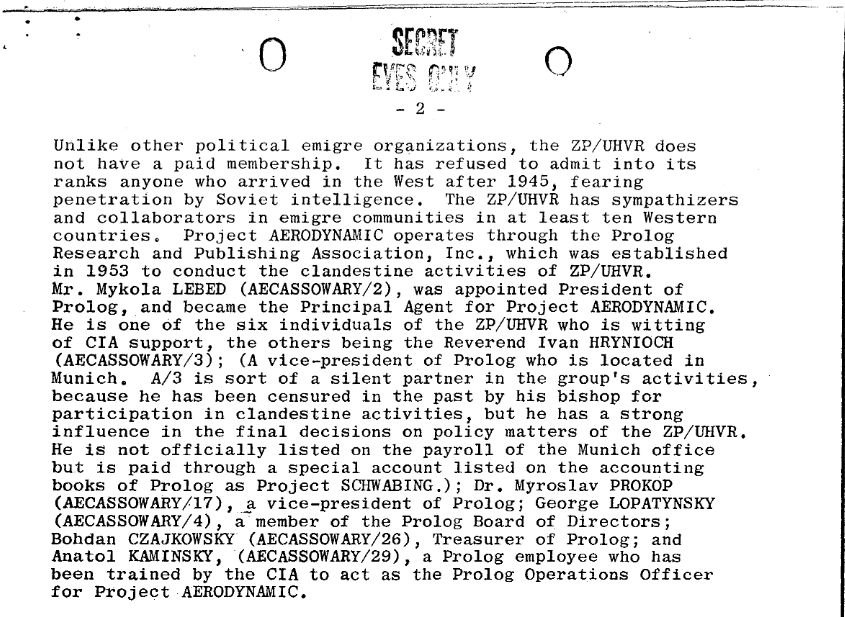

The CIA and the British MI6 began collaborating with the Banderites immediately after World War II. Today, the archives of the CIA’s Operation Aerodynamic have been made public. The USA made the OUN-member* Nikolay Lebed the key figure of this operation. Initially, small groups were sent to Ukraine for sabotage activities. But beginning with the 1950s, the CIA focused on propaganda work. The publishing group Prolog became a front for such activities showing high efficiency. This organization was engaged in transferring nationalist literature – publications such as Litopys UPA* [English: The Chronicle of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army* (UPA*)] – to the USSR, radio broadcastings, and recruitment.

The former Austrian claimant to the Ukrainian throne Wilhelm Franz von Habsburg-Lothringen, also known as Vasil Vyshyvaniy, was also engaged in establishing ties between the OUN*-members and the Western post-war leadership. Wilhelm had a very positive attitude towards fascism at one time. In 1935, upon his return to Austria, he wrote in one of his letters, “Here all is well and there is fascist law and order and ideologically it’s very pleasant.” According to the testimony of Roman Novosad, an OUN-member*, Wilhelm was in constant contact with the OUN-members* in Vienna during the war. Among other things, he used his connections in Austrian military circles to ensure that Roland’s fighters without sufficient combat training were not sent directly to the front and that they could return to their college studies “without reprisals” after the battalion was disbanded. After the war, Wilhelm established contact between the French and Lebed.

The Ostforschung experts, such as Hans Koch, Theodor Oberländer, as well as Boris Meissner, Dietrich André Loeber and others, actively opposed the Soviet Union after the war. They all deeply sullied themselves with National Socialism. During the war, Koch acted as a liaison between the Nazis and the Ukrainian nationalists. After serving in the Nachtigall, Oberländer was appointed commander of the Special Group Bergmann in the Caucasus and was jointly responsible for the war crimes there. Loeber served in the Brandenburgers special forces unit, to which the Ukrainian nationalist battalions had been subordinated. Meissner held senior positions in the Third Reich intelligence service and participated in punitive actions. Despite these facts, they worked for the German Foreign Ministry, in the German Embassy in Moscow and did research at the Universities of Göttingen, Cologne and Kiel during the post-war period.

Munich became the main post-war stronghold of Ukrainian nationalists.

In Munich, Hans Koch revived the Institute for East European Studies, previously located in Breslau. This institute publishes works by Ukrainian nationalists, including the extensive History of Ukrainian Culture [German: Geschichte der ukrainischen Kultur] by Mirchuk. The Ukrainian nationalist magazine Phoenix wrote later that this work was published in German by the Institute for East European Studies, headed by “Dr. Hans Koch, a well-known German scientist and a friend of Ukrainians.” The “friend of Ukrainians” Koch overstepped the bounds by publishing a book by Rosenberg’s former employee Heinrich Härtle under a pseudonym. This caused a scandal in the Bundestag. But Koch once again got away with this.

In Munich, Ivan Grinioch, former chaplain of the Ukrainian nationalist battalion Nachtigall and Lebed’s associate, headed a branch of the CIA-backed Prolog publishing group.

Kubiyovich, a collaborator and founder of the SS Division Galicia*, initially took refuge in Munich. He revived the Shevchenko Scientific Society there, of which Koch became a member. Later, Kubiyovich and his associates moved to Sarcelles in France, where they wrote the multi-volume Encyclopedia of Ukrainian Studies.

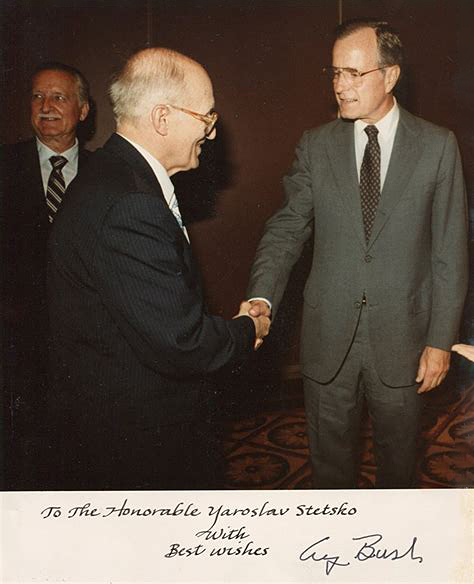

The former head of the “Ukrainian State” Yaroslav Stetsko also settled in Munich.

In exile, Stetsko and his wife Slava swung into action. Stetsko founded the Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (ABN) in 1946.

In 1958, Stetsko gave a two-hour speech to the US Congress about “subjugated nations.”

In 1959, the US Congressional resolution on the annual observance of Captive Nations Week was signed into law. This law mentions “Cossackia” and “Idel-Ural” among the “captive nations” – names memorable from the Nazi era.

The primary author of this law was the head of the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA) Lev Dobriansky.

A student and activist of the UCCA was Catherine (Kateryna) Chumachenko, the future wife of Viktor Yushchenko, who later became president of Ukraine.

By the way, Dobriansky’s daughter Paula was a friend of Chumachenko and held very high-ranking positions in the US government agencies. She served as under secretary of state during the presidency of George W. Bush in 2001–2009.

Stetsko participated in the creation of several anti-communist black structures. In 1966, Stetsko and the Asian Peoples’ Anti-Communist League (which had even earlier united the US-backed Asian right-wingers – Taiwanese leader Chiang Kai-shek and others) founded the World Anti-Communist League (WACL). The Nazi criminal Oberländer actively participated in the meetings of this league.

In 1977, Zbigniew Brzezinski, a Polish-American adviser to US President Jimmy Carter, would extend the work of Lebed’s highly effective Prolog to other ethnic groups in the USSR, including Jewish dissidents.

On July 19, 1983, Yaroslav Stetsko and other ABN representatives met with US President Ronald Reagan and Vice President George H.W. Bush at the Captive Nations Week observance ceremony in the White House. Reagan and Bush warmly welcomed Stetsko. During his speech at the event, Reagan stated, “Your struggle is our struggle. Your dream is our dream.”

It was the Nazis and Baderites who actively developed the theme of equating communism with fascism. In 1986, Canadian Markus Hess created the Black Ribbon Day Committee. The son of a German immigrant, Hess proposed to call the day of signing the Soviet-German non-aggression pact a day of remembrance of the victims of communism and Nazism. The World Congress of Ukrainians* (WCU*) endorsed his initiative. This organization was founded by the Ukrainian Greek Catholic priest Vasiliy Kushnir, who helped members of the SS Division Galicia* to exile after World War II. At the time of Hess’ initiative, the congress was headed by a former member of the SS Division Galicia* Pyotr Savarin.

Slava Stetsko endorsed the initiative by Hess and his associate David Somerville during a personal meeting, a photo of which was published in the OUN* bulletin.

Otto von Habsburg, the son of the last Austro-Hungarian Emperor Charles I, became a longtime ally of the Banderites in their initiatives. In the 1930s, the Austrian “heir” had close relations with the Austrofascists and secretly met with the leader of fascist Austria Kurt Schuschnigg. After the war, Otto von Habsburg became an active supporter of European integration and a member of the European Parliament. At the same time, he actively cooperates with Yaroslav Stetsko. Otto was honorary chairman of the so-called European Freedom Council (EFC) for many years, closely linked to Stetsko’s ABN.

At the initiative of Otto von Habsburg, the European Parliament adopted a Resolution on the situation in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania – a response to the so-called Baltic Appeal – on January 13, 1983. The resolution supported the appeal of 45 inhabitants of the Baltic republics to the UN, demanding to annul the accession of the Baltic States to the USSR. Encouraged by the adoption of this resolution, Otto von Habsburg gave a speech at a meeting of the European Freedom Council, in which he called on the “subjugated nations” to use such an instrument as the European Parliament “to your advantage.”

In the same 1983, Otto von Habsburg joined the international UPA* Honorary Committee, created by Yaroslav Stetsko in connection with the 40th anniversary of this organization. As the emigrant magazine The Ukrainian Review wrote, “Among the many distinguished political and military dignitaries from throughout the world, who consented to be members of this Honorary Committee, thereby honouring the fallen heroes of the UPA, are the following: H.R.H. Otto von Habsburg, M.E.P. — Honorary President of the European Freedom Council (EFC).” Other prominent committee members were retired US General John Singlaub (a senior CIA operative), US Senator from Arizona Barry Goldwater, and former British NATO’s Commander in Chief Allied Forces Northern Europe Walter Walker.

Congratulating Otto von Habsburg on his anniversary, Stetsko wished him “many long years in continuation of your most successful activities for the liberation of all the subjugated nations from the Russian yoke.” In connection with Stetsko’s death, Otto von Habsburg prophetically wrote that he “sowed seeds that will give fruit.”

With the active participation of Otto von Habsburg, the so-called Pan-European Picnic took place in 1989, which became the prologue of the unification of West and East Germany. At that time, the border gate between Austria and Hungary near Sopron was opened by mutual agreement. As a result, 600 GDR citizens escaped through this gate without being stopped by Hungarian border guards.

Otto von Habsburg had a special attitude towards Ukraine, the western part of which was once part of the Habsburg Empire. He insisted that Ukraine should become a member of the European Union.

It should be noted that the activities of former Nazis in the Baltics contributed to the Baltic republics’ secession from the USSR. In May 1989, Loeber personally organized a conference of “Popular Liberation Fronts” in Tallinn, where he gave a lecture on the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. The current Latvian president Egils Levits is a disciple of Meissner and Loeber. Levits recounted in an interview how these Ostforschung experts literally accompanied his studies in Sovietology, “I met Professor Loeber and Professor Meissner, who became my academic teachers. <…> Shortly before graduation, Prof. Loeber asked me: would you like to join the University of Kiel as a research assistant? Thus began my work at the Faculty of Law. <…> When I finished my lectures in 1989, I thought I would have to look for a job, but Professor Meissner called and asked me: would you like to start working at the Research Institute for Germany and Eastern Europe in Göttingen [Institut für Deutschland- und Osteuropaforschung des Göttinger Arbeitskreises]?”

In 1990, German Chancellor Helmut Kohl appointed another Ostforschung expert Boris Meissner to a delegation negotiating between the FRG and the USSR on the accession of a united Germany to NATO. These negotiations, in which Meissner had been directly involved as one of their ideologists, ended with the USSR unilaterally surrendering its positions and NATO moving closer to Russia’s borders.

In 1991, after the collapse of the USSR, Slava Stetsko came to Ukraine. After becoming a deputy of the Ukrainian Rada [Ukrainian parliament], she founded the nationalist party Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists (KUN), which trained many Banderites. The KUN’s co-founder was a US citizen Roman Zvarych, who had become Stetsko’s personal secretary back in 1979 in Munich.

As a result of the Orange Maidan in 2004, Viktor Yushchenko came to power in Ukraine. Then head of the US Freedom House Adrian Karatnycky, a member of the Ukrainian diaspora, actively shuttled between the United States and Ukraine, helping organize the Maidan. He would later describe his participation in August 2004 in a training camp that trained Maidan organizers, “Croatians, Romanians, Slovakians, and Serbians – leaders of the group that led civic opposition to Milosevic – taught Ukrainian kids how to ‘control the temperature’ of protesting crowds.”

Who were these “Ukrainian children” being trained by radicals from other countries?

(To be continued)

* – organization banned in Russia

Source (for copy): https://eu.eot.su/2023/09/12/ukrainism-who-constructed-it-and-why/

This is the translation of the lecture on the revised multi-authored monograph “Ukrainism: Who constructed it and why” first published in The Essence of Time newspaper, Issue 524. This research work was written by the members of Aleksandrovskoye commune, which is part of the School of Higher Meanings of the Essence of Time movement and is supported by the members of the Experimental Creative Centre International Public Foundation.

Dr. Sergey Kurginyan is a political and social leader of the Essence of Time movement, theater director, philosopher, political scientist, and head of the Experimental Creative Centre International Public Foundation.

Speaking about the topic of the monograph “Ukrainism: Who constructed it and why”, Sergey Kurginyan explained, “We are studying Ukrainism, not Ukraine. Our subject is Ukrainism as a construct. The creation of this construct, its characteristics, its consecutive transformation, its implementation, and finally its outlook―this is the focus of our study, which is thus fundamentally different from a normal historical or sociological study of a normal Ukraine”.