Mussolini — fully in the spirit of Sorel’s concept — began to create a party of “direct action” — a party of mass violence, supposed to embody the ancient Roman imperial myth.

Editor’s note: The fifth article of a series on essence, birth and rise of fascism. D’Annunzio’s Fiume Exploit taught Mussolini many things about what fascism should be like: what the leader must do, how the leader should effectively incorporate mysticism in his image, the role of mystical symbols and rituals that surround the leader, how to spellbind the crowd. D’Annunzio also made mistakes; Mussolini learned from his mistakes and became the Duce not of a single city, but of all of fascist Italy. XXI century Europe might give in to fascism despite all efforts – alas, fascist ideas might be dear to it’s people. Bringing fascists to power, with their solutions to immigration and economic crises, might be tempting to too many people. But this is the expectation of those who constructed these crises by bombing Libya and supporting extremists in Syria, by destroying the economies of some European countries in favor of the economies of others. Everyone who wants to fight fascism must be prepared. You, who want to fight fascism, will not convince anyone that you are right without deep intellectual understanding of fascism. We must learn to be convincing. And we are running out of time: hear the ticking of the clock, fascism gets closer by the second.

Let us emphasize one more time that it is Italian fascism which — for the first time in Modern era — gave life to the main concepts of “elite theory” and decisively and openly cancelled the fundamental principles of the French revolution — Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. The success of this attempt cannot be understood without the analysis of reasons and conditions of the rise of fascists to power. The devil, as they say, is in the details.

Which is why we will now discuss the details.

In the course of international conferences on redivision of the world after World War I, Italy, being one of the victors, received only a part of Italian territories promised to it by the allies for joining the war, territories earlier occupied by Austro-Hungarian Empire. Specifically, Italy didn’t receive back the regions of Adriatic shore in Dalmatia and Albania mostly populated by Italians.

This aroused a mass feeling of a “stolen victory” in Italy and a wide and acute wave of nationalistic revanchism.

The disappointment with the post-war situation was widespread and powerful. The spirits of “antiwar” socialists, Catholic “popolari”, nationalists, fascists were lifted by this disappointment — and tried to use it (with some success). Eventually, this mass disappointment was used to it’s fullest — even though not right away — exactly by Mussolini.

New members with combat experience started joining his fascist “league” during the war. On March 23, 1919, Mussolini held a founding congress of the fascist party Fasci italiani di combattimento (“Italian Fasci of Combat”).

Mussolini did not have a clear political platform at that point. More than that, Mussolini, remembering the success of his sharp pre-war political “repositioning” from anti-war internationalism to militaristic nationalism, has stated in his speech during the founding congress of the party (clearly with a reference to Machiavelli): “We permit ourselves the luxury of being aristocrats and democrats, conservatives and progressives, reactionaries and revolutionaries, legalitarians and illegalitarians, according to circumstances of time, place and environment in a word of the history in which we are constrained to live and to act.“

Mussolini declared recreating the glory of Italy as the new Roman Empire the main goal of the party. Fasces were chosen as the symbol of the party and Mussolini declared the creation of “combat units” as one of its foremost tasks. Which means that Mussolini — fully in the spirit of Sorel’s concept — began to create a party of “direct action” — a party of mass violence, supposed to embody the ancient Roman imperial myth.

The fascist party started to quickly gain support both in cities and villages. But Mussolini instantly faced serious competition in the far right political field.

The competitor was the already mentioned Gabriele D’Annunzio. Who, despite his well-known moral impurity (left his wife, had dozens of mistresses, didn’t pay his debts, lied, fled from his moneylenders, tricked publishers, etc.), became the most read and respected Italian poet and writer even before World War I.

When the war started, D’Annunzio was among the first to support radical “imperial” interventionism and was the first to widely use — notably, in deliberately theatrical fashion — the ancient Roman myth. At the time D’Annunzio comes to his crowded rallies dressed in a Roman toga, urges Italy to fight for rule over the “mare nostrum” (as the ancient Romans called the Mediterranean), revives the salute of ancient Roman legionnaires among his supporters — raising the palm of their right hand up.

When Italy joined the war, 52-year old D’Annunzio volunteered for the navy. He and his torpedo boat unit soon conducted the first of its kind boat attack against a naval base — Austrian harbor of Bakar. This attack was pointless in the militarily speaking: there were no ships in the harbor at the moment. But D’Annunzio’s raid caused political outcry both in Italy and the world.

D’Annunzio left the navy to join the air force where he became one of the most well-known pilots. And not because of his literary fame: he was a risky, bold and effective fighter. A year after the raid on Bakar — again, for the first time ever — he conducts another operation which is well-known in military history. D’Annunzio started the age of long-range bombardment aviation by dropping leaflets on the capital of the enemy, Vienna.

He earned a rank of lieutenant-colonel by the end of the war. D’Annunzio resigned, being very popular both among the military (especially the elite units) and the broad Italian masses, including millions of discharged soldiers and officers. King Victor Emmanuel III and the government wanted to bring such a politically valuable person to their side: D’Annunzio was offered a rank of Marsh of the air forces and the office of Deputy Prime Minister. But the prudent and cynical D’Annunzio didn’t want to become associated with the weak and careful government.

When it became clear in 1919 that the allies decided to hand the ancient Italian city of Fiume not to Italy, but to the newly created Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (the future Yugoslavia) during the talks in Versailles, a delegation arrived to D’Annunzio from Fiume and offered him to take over the leadership of the resistance.

D’Annunzio first tried to persuade army commander Pietro Badoglio and the king to solve the problem of Fiume with military means. But when they refused he accepts the offer of Fiume residents and starts his “march”. At the same time, D’Annunzio offers Mussolini to join forces and send his fascists to “march to Fiume”. But Mussolini didn’t give a clear “Yes”. He wasn’t ready to decisively oppose the government. And, besides, he understood that in this case both he and his party will be following the head of the “march” in the political sense.

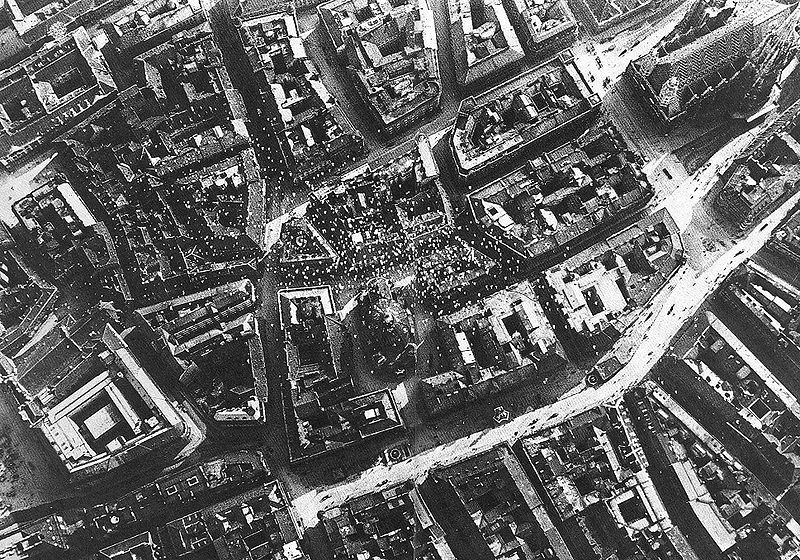

The “Fiume Exploit” started on September 11, 1919. D’Annunzio was riding first, in a “Fiat” covered with rose petals, with fifteen trucks of his “army” following him. They were mostly armed supporters of the leader, former army storm troops, the so-called “arditi” (“the daring ones”). Soldiers and refugees joined the march on the road. On the border they were joined by a general of the Expeditionary Forces in Fiume, together with the troops which were supposed to stop D’Annunzio.

D’Annunzio triumphantly entered the city, declared himself “Comandante” (this rank was later adopted by many revolutionaries, mostly anarchists) and became the real owner of Fiume. He declared to the residents of the city: “Italians of Fiume! In the insane and cowardly world Fiume is now the beacon of freedom… We are a handful… of mystical makers who are destined to sow the seeds of new power, which will grow to become the crops of desperate daring and fierce revelations“.

The government had to react to such a scandalous arbitrary behavior: Prime Minister Nitti orders the troops to surround the city. But the army had already fallen to D’Annunzio’s propaganda and didn’t undertake any military action against him. Then not only “arditi”, but also army deserters, as well as different kinds of bohemian artists and simply leisured rabble started to come to Fiume from all corners of Italy. Finally, captains of warships blocking Fiume from the sea joined D’Annunzio in September 1919.

After which D’Annunzio wrote a letter to Mussolini which finally determined how the future dictator treated his competitor: “I am equally amazed by You and the Italian people… You whine… we struggle… Where are Your fascists, Your volunteers, Your futurists?… Wake up! Pierce Your belly and blow down the fat. Otherwise I will do this myself when my rule will become absolute.“

Mussolini sent money and squads of his fascists to Fiume, wrote enthusiastic articles about Fiume. But he never forgot this letter he received from D’Annunzio.

Meanwhile, D’Annunzio turned life in Fiume into a theatrical show. First he personally wrote a draft constitution — in verse. Only being pressured by his supporters he assigned drafting of the constitution to his “Prime Minister”, but included such articles in it as mandatory musical education for children, official state cult of muses (and building temples for it), special “soft” laws (the most harsh of which was banishment of the criminal from the “free city”) and so on.

D’Annunzio invited the great conductor Arturo Toskanini to be his Minister of Culture, appointed the Belgian anarchist poet Leon Kokhnitsky to be Minister of Foreign Affairs, and an opportunist with three criminal records to be Minister of Finance. He also introduced the scarlet state flag of Fiume depicting the Ursa Major constellation encircled by the mythical snake Uroboros biting its own tail. At the same time — like in ancient Rome — divides his arditi into legions, cohorts, manipulas, etc.

Endless parades of arditi and residents in black shirts under the banners depicting a dead head took place in the city, bands played on squares, songs written by comandante were being sung. D’Annunzio constantly makes inflammatory speeches before the residents of the city, sometimes several times a day. Contemporaries noted that nobody was such a master of the magic of public speaking as D’Annunzio: his speeches, quite simple and uniform in content (usually containing a large dose of mysticism), spellbound the audience and caused it become literally ecstatic (by the way, this is exactly the Le Bon’s “effect of the crowd” which I described earlier).

The nights in “free Fiume” in essence turned into a non-stop carnival in the spirit of Rabelais — rollicking dances, debauchery, alcohol abuse, drug abuse every day until the very morning.

Since the city was mostly “charging itself with ideology” and having fun, but produced almost nothing, there was often nothing to eat. D’Annunzio solved this problem by sending warships that swore allegiance to him to pirate across the Mediterranean Sea. However, there still was not enough bread; cocaine started to be generously distributed to residents right on the streets “in order to give them strength and lift their spirits”. Comandante himself quickly got addicted to it.

Of course this strange harmony of a “free pirate republic” could go on only as long as the Italian government needed such a Fiume for political bargaining with the allies. According to the Treaty of Rapallo of November 12, 1920, the main territories of Dalmatia, including Fiume and the surrounding area, were handed to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. After which the government forces and Italian cruiser have blockaded Fiume. D’Annunzio surrendered the city on January 2, 1921, after being guaranteed the all residents will be pardoned. Soon after he returned to his motherland — this time humbly and with a small number of guards. Meanwhile, the socioeconomic and political situation in Italy was steadily escalating.

War left Italy with an “overblown” defense industry, large military loan debts and without new colonies which could have become a source of raw materials for industry and an emigration zone for excess population.

The situation in the villages was especially difficult. The villages of the primarily rural Italy didn’t receive almost any of military subsidies; at the same time, over 3.5 million men have returned there out of a total of 4 million war veterans.

There was traditionally little trust to the Parliament and the government in Italy, but after they “lost the victory” it crumbled altogether. The role of “grassroots democracy” represented by local trade union-syndicates and leagues, people’s banks, rural mutual financial aid organizations, production cooperatives and socialist unions and so on was growing all over the country. It were these half-spontaneous “grassroots” unions of workers that had to solve the growing practical problems of organizing the survival of their members.

And it was getting harder to solve these problems with the growing economic chaos and with the clumsy and inconsistent attempts of the government in the capital to overcome it. Both the elites and the broad masses demanded order. And the deeper the crisis was, the higher the demand for order was.

Mussolini attentively watched D’Annunzio’s actions for the whole period of “Fiume republic”. He digested and adopted his dramatic techniques — from black shirts to solemn parades of his supporters who saluted by rising their right hand, and from the mysteriously-mystical symbols of the rituals of the leader to the magic of words of his powerful speeches during rallies. He understood that all of this is very important. He also understood that Fiume had a leader and the necessary fascist style, but there was no order and no work. That a lone bohemian aristocrat with Nietzschean psychology didn’t solve the task of order and work and that he wasn’t going to solve it. Which is why he was just talking about absolute rule.

Mussolini, on the other hand, wanted to receive this absolute rule. And persistently worked on creating a powerful organization. If the numbers of his fascists did not exceed ten thousand men in 1919, his party had over one hundred thousand members by 1921. And these members were, unlike D’Annunzio’s “Fiume precedent”, united by party hierarchy and discipline.

The situation was also in Mussolini’s favor.

Liberals and democrats were crushed during the November 1919 Parliamentary elections. Socialists gained the majority in the Parliament (156 seats) together with the Catholic popolari (95 seats). But… the winners instantly refused to cooperate because the socialists categorically adopted the motto of Russian Bolsheviks: “Land to the peasants, factories to the workers”. And waves of mass revolts started across the country. Peasant syndicates and associations in the south took over and divided the lands of latifundists, rich landholders and rich peasants. Many factories were seized by the workers by fall 1920 in the north.

This is where Mussolini’s fascists squads — “squadre” — became in-demand.

Source (for copy): https://eu.eot.su/?p=3126

This is the translation of the fifth article (first published in “Essence of Time” newspaper issue 57 on December 4th, 2013) by Yury Byaly of a series on essence, birth and rise of fascism. Part 1: Marxism, imperialism and the justification of inequality. Part 2. Part 3. Part 4.