Inequality was impossible to justify within the boundaries of revolutionary victorious bourgeois liberalism (with “Liberty, equality, fraternity” on its banners). Which meant that the only way equality could and had to be justified is anthropologically.

Editor’s note: Below is a translation of an article by Yury Byaly. The article “Marxism, imperialism and the justification of inequality” was originally published in the 52nd issue of “Essence of Time” newspaper on October 30, 2013. This is the first article in a series on the theory of elites, birth of fascism and Nazism. The articles of Yury Byaly are dedicated to the study of conceptual warfare – a part of non-classical warfare.

“Communism, liberalism, fascism and all other “isms”, the struggle between which is called ideological warfare, do not attack history itself. They try to direct the stream of history in one channel or another. Conceptual warfare is not the war for the channel in which the historical energy will flow. This is the war against history as such.”

When it comes to building the mighty German state, the role of Otto von Bismarck is acknowledged not only by the friends of the “Iron Chancellor”, but also by his enemies. But both friends and enemies of this unifier of Germany, who has declared that the state is built with iron and blood, are not too prone to discuss what was the state that Bismarck built. Both agree that Bismarck built a mighty state, overcame the differences between the pre-bourgeoisie elites (first and foremost – the Prussian military aristocracy) and the rising new bourgeoisie elites. But that is it. Even Lenin – one of the deepest analysts of his time – did not think it necessary to analyze Bismarck’s model in detail when he was drawing parallels between Bismarck and Stolypin, having put it alongside Marxism.

In the mean time, it is difficult to discuss the essence of Marxism and the real alternatives to the development of humankind in the XXI century without such an analysis.

The first feature of Bismarck’s model – a highly restrained attitude towards colonial conquest.

Having completed the political unification of loosely knit German territories in 1871, and having celebrated the victory over Napoleon the Third’s France, Bismarck rejected the offers to join the far-from being consolidated German empire into the “scramble for Africa”. Why? Because, Bismarck stated, the best colonies are already divided between the imperial competitors. Which means that the costs Germany will have to pay if it wants to join the repartition of the colonial periphery of the world will greatly outweigh the gains. Because Germany will have to go to war against the greatest world powers – Great Britain, first and foremost.

But Bismarck was being somewhat evasive when he justified his anti-colonial position with the difference of gains and losses which have to do with colonial conquest. An attentive review of his model makes tells us that he was looking ahead and realized the instability of states built on the colonial principles. And clearly wanted to oppose this fundamental colonial principle with another, no less fundamental principle.

Bismarck filled his “Prussian state socialism principle” (meaning another model of socialism, not in any Marxist) with a quite distinct anti-colonial content. After all, colonial expansion really did require large resources to be invested in military-oriented industries, which inevitably lowered the standards of living of the majority of the population. What does such a lowering mean? It means that the working class and other disadvantaged groups of population cannot be properly lifted (or, as Marxists said, bribed).

However, it doesn’t even matter in this case if it was all about simply bribing the working class or about integrating it into some sort of special Bismarckian “society of collective welfare”. The point was that both such bribery, and such integration requires resources. And Bismarck didn’t want these resources to be spent on colonial conquest and the big wars such conquest always leads to.

However Bismarck was only a Chancellor, not the Emperor. His political capabilities were not unlimited. In 1884, under the pressure of leading governmental groups he had to declare that a number of African territories already taken over by the German enterprises (meaning, potential colonies) are under the protection of the Empire. This is how the Germany acquired its colonies and protectorates: German South-West Africa (modern Namibia), German Cameroon, German East Africa, Witu (German Kenya) and others.

Nevertheless, Bismarck, as long as he had the decisive influence over the politics of the German Empire, used this influence to restrain German colonialism. And, in essence, viewed German colonies only as a bargaining chip with colonial competitors. This way, he had in essence simply traded Witu colony for Heligoland island in the North sea, which he considered to be a strategically key locality of the Empire in its competition against England.

Kaiser Wilhelm II launched the second stage of colonial expansion in 1890’s after Bismarck resigned, and immediately faced serious domestic political challenges.

The second feature of Bismarck’s model which is important to us – rejection of the idea of war with Russia.

The third feature – opposing Marxism not with one or another anti-socialist model, but with a new original model of “state socialism”. Had Bismarck managed to hold Germany in the frame of such strategy, perhaps, all of 20th century history would have been different. But, alas, the role of the individual in history has its limits and Bismarck’s position was in some sense politically precarious. As a result, the mediocre Wilhelm II dismissed the genius Bismarck. And instantly faced the same domestic political challenges his Italian political doubles had faced, being as much as banal (if not worthless) as he was.

Just like Germany, Italy has completed the unification of territories into the Kingdom of Italy only in 1871. At the same time the formal unification was far from stopping the rivalry of regional (dynastic, economic, political) groups for the positions in the Kingdom. Which is why Italy was only able to launch colonial expansion in the end of the century: first on the Horn of Africa (annexation of Eritrea in 1885 and part of Somalia in 1889), then in Northern Africa (annexation of Libya after the war with Turkey in 1911-1912).

However, the very first colonial wars have caused serious domestic social-political “tensions” in Italy which had to do with the activity of Red political powers.

Since, as soon (and we have discussed this above) as the reunited capitalistic state starts to withdraw domestic resources in favor of colonial conquest and wars, the state loses its strategic ability to act independently in everything which concerns the unity of nation and the harmonization of relations between labor and capital.

The Red forces (socialists and communists) start pushing the hot button, pointing out that the resources required for such a harmonization are being withdrawn for heaven knows which purposes… And what is there to reply? Of course, these so much uncomfortable Reds can be simply repressed. But… such repression is pregnant with most serious political and other costs, which was clearly demonstrated by the experience of French, Italian, German and other revolutionary outbursts in the second half of the 19th century.

Which is why the groups in the authority couldn’t not have been in a search for a “conceptual antidote” to the more and more influential “socialist” concepts of proletarian solidarity and internationalism.

Where such “antidotes” were sought first and foremost?

The theoretical indulgences in the area of social-Darwinism and “racial struggle” made it clear what the main strike was directed at. The main strike was against that concept (blessed first by Christianity, then by the Great Bourgeois revolutions!) which socialists and communists have followed to its logical end. The concept of fundamental – anthropological – equality of humankind.

It would be hard not to acknowledge that humankind spent all of its history under the sign of social human inequality, with the “rule of chosen ones” being justified by this inequality. This way, for example, over two thousand years ago Plato (“The Republic” dialogue) and Aristotle (“Politics” treatise) in Greece, Confucius (“Analects”) in China, Vishnugupta (“Arthashastra” treatise) in India had claimed and justified social inequality, as well as constructed various models of “ideal governing” taking this inequality into account.

However, according to both Plato and Confucius, the rulers must be, first of all, only the worthiest and moral of all, and, secondly, only pursuing the goals of the common good. To add to this, according Plato and Vishnugupta the worthiest are defined aristocratically – based on their descent, as well as noble upbringing and education; but according to Confucius the “low-born” was also able to become the worthiest and rise along the power structure thanks to hard work, talent and being ready to serve the common good.

The great Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) have admitted the equality of all people before God (which is the anthropological equality), but made an exception. This exception is mostly developed in Catholic Christianity. Its essence is that the right to rule was made sacred by the Pope, the Vicar of Christ, and was granted to the monarchs. The monarchs, through the Pope’s anointment, as if became a part of God’s rule and have delegated a part of their authority down the power hierarchy “pyramid”: to princes, dukes, counts, barons and so on – to the “ancestral aristocracy”.

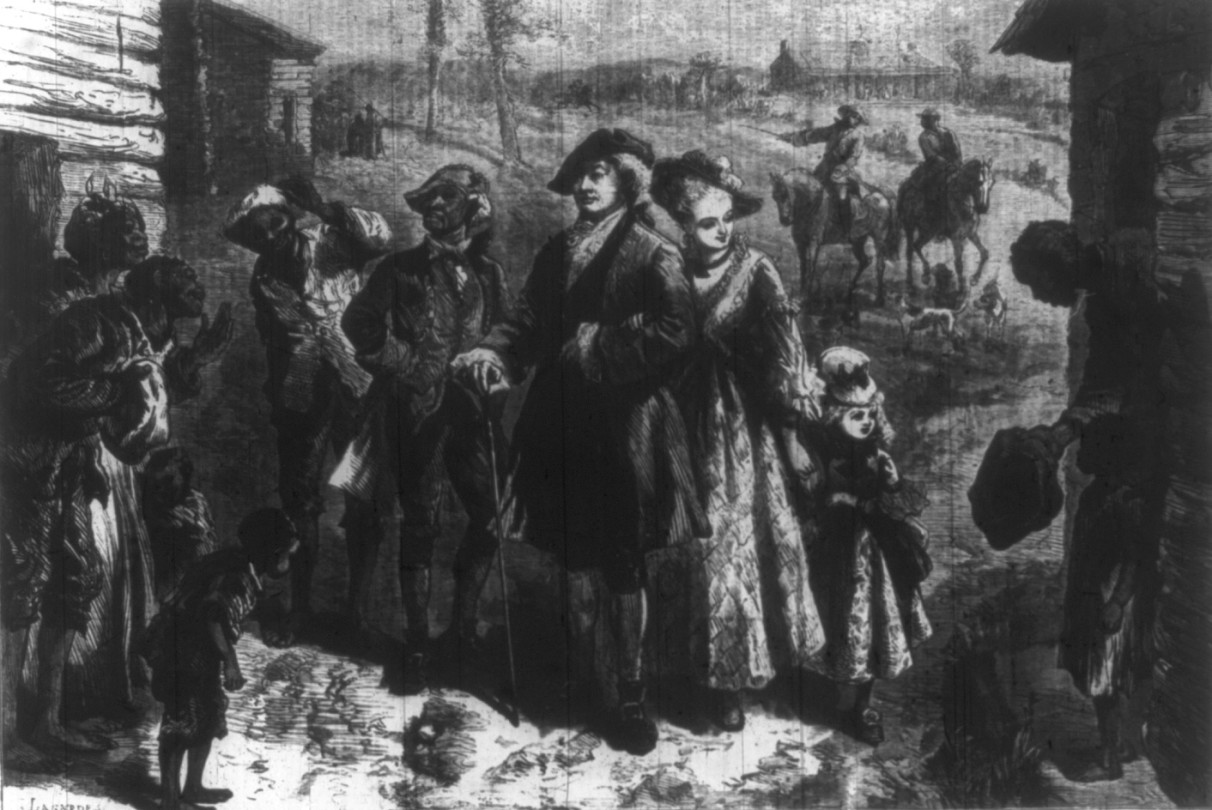

Protestantism, as we have discussed earlier, refused to recognize the “divine right” of the Pope. Which means it destroyed the basis of centuries-long ruling hierarchy of “ancestral aristocrats” blessed by Catholicism. The Bourgeois revolutions of the Modern era, the Dutch, English, and the French revolution, took place exactly under the banner of anthropological equality of all humans. It is the French Revolution that proclaimed Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. That same French Revolution had soon decisively brought the “aristocracy of wealth” (to some extent, the aristocracy of the labor of productively using wealth), the bourgeoisie, to the top floors of power.

The majority of the “ancestral aristocracy”, having lost a major share of its power to the rising (mainly “lowborn”) bourgeois class, had to yield. But quite a few of its members were dreaming of revenge. It was especially evident in France, with its several restorations of monarchy after the French Revolution.

The proletariat became an organized political power in the last third of the 19th century (chiefly thanks to Marxism, of course), declared a proletarian revolution as its goal and formulated its principles of true “collectivism of equality”, proletarian solidarity and internationalism. Meaning, became just as a real threat to the rule of bourgeoisie, like the threat bourgeoisie had earlier become to the rule of aristocracy.

Exactly at this moment the imperialistic bourgeoisie felt the need for the not fully defeated aristocracy to become its intellectual and political ally against socialists and communists. The tasks of “justifying power through inequality” were set in such – recently unthinkable of – unity of goals.

But how can this be done? Inequality was impossible to justify within the boundaries of revolutionary victorious bourgeois liberalism (with “Liberty, equality, fraternity” on its banners). This means that equality could only be attacked together with liberty and fraternity. Which means? Which means that it can be attacked only anthropologically. Because anthropological equality really is the basis and condition to human liberty and fraternity (that same Marx’s “true collectivism”). If there is no equality – there can be no fraternity, no liberty.

Aristocracy had old conceptual basis in its arsenal for attacks against both the equality, and liberty – radical versions of Gnosticism, with its precisely anthropological inequality. We will talk about Gnosticism, which used to be the primary – and very powerful – conceptual and even metaphysical enemy of Christianity in the first centuries A.D., later. It is worth noting here that racial theories of aristocrats Joseph de Gobineau and Houston Chamberlain, which we have discussed earlier, have clearly Gnostic roots.

At that moment, however, racist concepts were difficult to transfer to the national soil and put to use against the main enemies – socialists and communists. Try and justify criteria, according to which they have to be acknowledged “racial strangers” in their own country! Nobody yet dared to do such a thing in the end 19 – the beginning of 20th centuries.

Which is why the anti-communistic alliance of “ancestral aristocracy” and imperialistic bourgeoisie turned to more convincing for the masses of that time “scientific” justifications of inequality. That is, to the sociology of authority, and more specifically, to certain types of the so called “theory of elites”.

It is important to highlight that the “theory of elites” is quite a honorable science. It admits that a special function of socio-political, economical, state governance is bound to appear in a complicatedly organized society. Which means that a special group which executes this function necessarily exists – the ruling class, or the elite. Which means that objective inequality of “ruling and the ruled” is bound to exist.

Many things are necessary to be studied, then. The functions of the elite and the demands to its quality… The principles and conditions of the development of the elite… Criteria of its adequacy to its role… The risks of degeneration or transformation of the elite, when it either turns out to be unable to execute its functions of governance, or substitutes the goals of its governance, disregarding the common good (according to Plato or Confucius) in favor of its political, economic and power gains… The structure of the society and ways to govern the society and the state which allow the elite to execute its governing functions in the best way possible… And so on.

We will discuss the results of this research and how these result were used in the “war against equality” in the next article.

Source (for copy): https://eu.eot.su/?p=2592

We encourage republishing of our translations and articles, but ONLY with mentioning the original article page at eu.eot.su (link above).