(Links to previous Chapters are available here: Preface, I, II, III)

One idea from the 1920s is still alive today: that a pan-European transition from modern EU democracy to some kind of pan-European monarchy is possible. And in the case of such a transition, the Habsburg dynasty is without rival.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, monarchist movements emerged in Russia, as well as in many Eastern European countries where monarchies once existed. Unlike these other Eastern European countries, in Ukraine, the monarchist topic did not get much attention either in the late-Soviet or post-Soviet times for a quite understandable reason – it has no real, sufficiently strong and attractive, monarchist tradition.

Nevertheless, there are forces that are interested in the possibility of establishing a monarchy in Ukraine. They can be tentatively divided into three groups: 1) the “Old Kiev” group, 2) “Hetmanite” group, 3) those oriented towards restorating the monarchical traditions of those countries that once included parts of the contemporary Ukraine. In the latter case, the monarchical tradition of Austria-Hungary, i.e. the Habsburg-Lorraine dynasty is first and foremost.

To begin we will briefly characterize each of these groups. We shall then discuss the Habsburgs, who lost the throne after the collapse of Austria-Hungary, and their views of Ukraine in greater detail.

Proponents of the “Old Kiev” group are ready to consider a representative of the Rurik dynasty, an heir of one of the princely families of ancient Kievan Rus’, as a potential Ukrainian monarch. However, the proponents of the “Old Kiev” group have no specific figure that could be considered a serious claimant to the throne of Kiev. This also applies to the descendants of Daniel of Galicia, the ruler of the principality of Galicia-Volhynia and the first “king of Russia” [in the Western literature “king of Ruthenia”. As it was explained in Chapter III, the term “Ruthenian” was invented in Austria-Hungary as a tool for the Ukrainization of the Rusyns – the Western Slavs – translator’s note] (Rex Russiae – such title he received from the Pope at his coronation in 1254).

The representatives of the “Hetmanite” group refer to the times of the Hetman State [also known as the Second Hetmanate – translator’s note], a state entity that arose in 1918 and lasted a few months [the establishment of this state is discussed in greater detail in Chapter I – translator’s note]. Pavel Skoropadsky, “the Magnificent Lord Pan Hetman of All the Ukraine,” in his memoirs wrote that Metropolitan of Kiev and Galicia Antony Khrapovitsky offered to anoint him as tsar. The anointing did not take place. But this did not prevent Skoropadsky’s supporters, already in exile, from developing the concept of Ukrainian monarchism.

Its author is considered to be Vyacheslav Kazimirovich Lipinski, a Pole by nationality from an old Polish noble family, a philosopher and essayist, and an ardent supporter of Ukrainian conservatism, in other words the “Hetmanite movement”.. In his historical-philosophical work, written in Polish, justifying the role of the Polish gentry, the Szlachta, in Ukraine (the work was called “The Szlachta in Ukraine”), Lipinski advocated for such Ukrainian statehood, in which the Polish gentry – landowners would play the key role, acting as “native sons of this land,” rather than as colonizers.

In 1912, Lipinski’s major works were published under the title “From the History of Ukraine,” in which this ideologue advocated the idea of a Ukrainian constitutional monarchy, the head of which, according to Lipinski, should be a hetman by birthright, a Ukrainian monarch. Proponents of Lipinski’s theory, placing their bets on a monarchical hetmanate, sought to establish the legitimacy of Skoropadsky’s blood heirs. The other part of the “Hetmanite” group adhered to the idea of an elected monarchy.

In the 1930s, Skoropadsky, who lived in Germany at that time, had several meetings with Hitler.

In 1944, Himmler proposed to Skoropadsky the foundation of the Ukrainian National Committee, which would be part of the “Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia,” headed by General Vlasov. Skoropadsky said that to discuss this issue, it was first necessary to free the Ukrainian nationalist leaders from the Sachsenhausen concentration camp, where they had been placed as political prisoners after they had arbitrarily adopted the “Act of the Proclamation of the Ukrainian State” in German-occupied Lvov on June 30, 1941.

In November 1944 negotiations were held at Skoropadsky’s house in Wannsee, where besides Skoropadsky himself, the head of the OUN-M [Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists] (organization banned in the Russian Federation) Andrey Melnik, the head of the OUN-B (organization banned in the Russian Federation) Stepan Bandera, Bandera’s deputy Yaroslav Stetsko, and the president of the UPR [Ukrainian People’s Republic] in exile Andrey Livitsky took part. These talks, however, ended in nothing.

In April 1945 Skoropadsky died after being fatally wounded near Munich during an Anglo-American air raid.

In subsequent years, the Hetmanite movement gradually declined and by the time of the establishment of an independent Ukraine it was no longer a real political force.

As for the idea of a representative of the Habsburg dynasty taking the throne in Ukraine, we should begin with the fact this idea is not new. An attempt to create a monarchy in Ukraine and to place a Habsburg on the Ukrainian throne already took place in 1918, during the Civil War.

It is noteworthy that shortly before that, during World War I, the role of monarch of the puppet Kingdom of Poland (which, unlike the Ukrainian monarchy, was actually founded in 1916 by Germany and Austria-Hungary) was claimed by the father of Wilhelm Habsburg – Archduke Carl Stephen of Austria. Let us begin by discussing this figure and this Polish project.

Charles Stephen of Austria and the puppet Kingdom of Poland

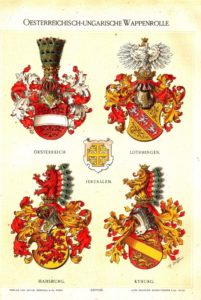

Archduke Charles Stephen of Austria (1860-1933) belonged to the cadet – Teschen – branch of the Habsburg-Lorraine house. He was the third cousin to the reigning Emperor of Austria-Hungary Franz Joseph I.

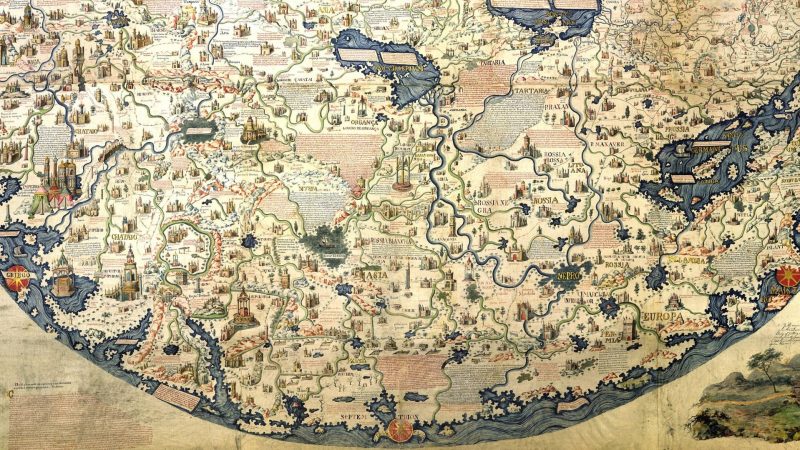

As admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Navy, Charles Stephen had a well-developed political and military sagacity. He was aware that the creation of nation states was on the world agenda. There were striking examples before his eyes: in 1861 the disparate Italian states merged into one country under the Sardinian kingdom, and in 1871 a unified German empire emerged. The existence of the multi-ethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had accumulated many internal as well as external problems, did not seem unshakeable to Charles Stephen. The likelihood of war between Austria-Hungary, Germany, and the Russian Empire was high. Charles Stephen understood that if such a war broke out, Poland (parts of which became part of the three above-mentioned states after the partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth) might have a chance to be restored.

Whether Charles Stephen was ambitious or there were some other motives, but being aware of the instability of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the potential of Poland, he consciously formed in his children not an imperial, but a Polish national identity. Charles Stephen raised his older sons Polish in language and spirit, and he married off two of his daughters to members of the Polish gentry. Only Charles Stephen’s youngest son, Wilhelm (the future Vasil Vyshyvaniy), linked his fate not with Poland, but with Ukraine. However, with all the importance of this figure for us, it is advisable to begin the discussion of the Habsburgs’ claims to certain thrones with the claims to the Polish, and not the Ukrainian, throne.

August 2, 1914, immediately after the outbreak of World War I, an appeal to the Poles was published by the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian army Grand Duke Nikolas Nikolayevich, which promised to reconstitute a unified Poland (divided in the late 18th century between Prussia, Austria and Russia), granting it self-government within the Russian Empire.

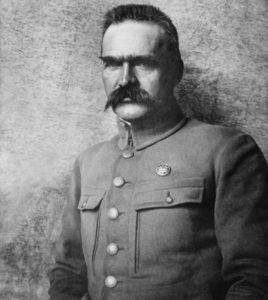

Some Poles were quite happy with this option. However, another part did not want Russia to win, and hoped that the unification of Poland would take place if Russia was defeated. The Polish Socialist Party headed by Józef Piłsudski, for example, adhered to this view.

In the summer of 1915, the lands of the Congress Kingdom of Poland, which was part of the Russian Empire, were occupied by German and Austro-Hungarian forces. However, neither Germany nor Austria-Hungary sought to reconstitute “Greater Poland,” as this would have required them to return to the Poles the territories that had fallen under Germany and the Austrian Empire after the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The maximum that Austria-Hungary did was to grant Galicia a broad self-government within the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Nor were the Germans going to give up the Polish lands that they obtained as a result of the partitions of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

When the Germans and Austrians occupied the Congress Kingdom of Poland, they divided it into German and Austrian zones. Germany began to actively export labor and imposed compulsory supplies of food at fixed prices, resulting in a famine in Poland in 1915.

In the summer of 1916, when the military situation of Germany worsened (the Russians successfully advanced in Volhynia and Galicia), the German government decided to go for the foundation of a puppet Kingdom of Poland in the occupied Polish lands that were part of Russia. This construct was created by Germany with the very specific goal of forming a Polish army that would enter the war on the side of the Central Powers. It was estimated by German military experts that about 1 million people could be put under arms in Poland. The creation of an ostensibly independent kingdom was necessary because of the norms of international law, which prohibited the mobilization of the population of the occupied territories.

In August 1916, German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and Austrian Foreign Minister Burián agreed that Germany and Austria-Hungary would not only retain the Polish lands they had previously obtained, but would also add to them some lands of the occupied Kingdom of Poland. Specifically, Germany intended to annex the “Polish frontier strip” – the territory in which the cities of Częstochowa, Kalisz, Plock, and Mława were located. The Germans intended to evict the local population – Poles, Jews, and others – from the borderland and repopulate it with Germans. The purpose of such actions was to create a “German strip” between the Kingdom of Poland and the Poles living in Prussia.

On the remaining part of the Congress Kingdom of Poland, the Kingdom of Poland was to emerge. It was assumed that this puppet state would have no foreign policy of its own and that its army would be completely under the control of Germany.

At the suggestion of German Emperor Wilhelm II, Archduke Charles Stephen, the father of the future Vasil Vyshyvaniy, was to ascend the throne of the Kingdom of Poland. However, Emperor Franz Joseph I had other plans – he hoped to incorporate the reconstituted Poland into Austria-Hungary. So he did not give his consent to the candidacy of Charles Stephen (and without the consent of the head of the Habsburg-Lorraine House a representative of the dynasty could not ascend the throne). The question of who would get the crown of the newly created Kingdom of Poland was left in limbo.

On November 5, 1916, the German Military Governor General Hans Hartwig von Beseler and the Austro-Hungarian Military Governor General Karl Kuk made a statement about the intention of the monarchs of Germany and Austria to create the Kingdom of Poland on territories “wrested with great sacrifices from under Russian domination”. It was announced that the Kingdom of Poland would become “an independent state with hereditary monarchy and constitution”. At the same time the definition of the borders of the state was postponed to the future. On the other hand, it was immediately stated that the state was in alliance with the Central Powers.

Stefan Krzywoszewski, a Polish writer, journalist, and playwright who was present at the proclamation of the Manifesto to the Polish Nation on November 5 at the Royal Castle in Warsaw, recalled:

“The German orchestra, invisible at the end of the hall, played Boże coś Polskę and Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła (Polish national anthems – D.S.). We, Poles, had struggled for breath as a strange feeling seized us. We were witnesses to an act of great importance, the first step toward independence. We were given back a part of the Fatherland, but such a modest one! And even then, under an invader’s rule that might have been a worse yoke on us than the previous one. All together – this historic hall, the crowds of Polish nobles, the sight of invading crusaders, the beloved folk songs sung by German soldiers – was it not a nightmare dream, a bloody mockery of our dreams of a free, united Poland?”

On November 21, 1916, the aged Emperor Franz Joseph I died. But the late emperor’s grandnephew Charles I of Habsburg-Lorraine, who ascended the throne, was also in no hurry to make Archduke Charles Stephen ruler of the Kingdom of Poland.

In January 1917, an advisory body was created in the Kingdom of Poland – the Provisional Council of State – of 25 people, 15 of whom were appointed by the German government and 10 by the Austro-Hungarian government. Of the people respected in Poland, only Piłsudski was included in the Council. However, when Piłsudski learned of the intention of Germany and Austria-Hungary to create a Polish army for their own needs, moreover, subordinate it to Germany, he expressed his categorical disapproval and withdrew from the Council.

Consequently, the hopes of the Central Powers for a separate Polish army completely failed along with the recruitment of volunteers.

In August 1917, the Provisional Council of State resigned. It was replaced in September 1917 by the Regency Council, the collective supreme authority, aimed to perform its functions until they were transferred to the hands of the regent or the king. In reality, the rights of this body were minor, the Chief of the Civil Administration in Warsaw, Otto von Steinmeister, and Military Governor General Hans von Beseler were the real power.

On February 6, the Regency Council issued a decree on the establishment of the Council of State of the Kingdom of Poland, which was assigned the role of an interim parliament. This body, however, did nothing significant.

The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed by the Central Powers and the Ukrainian People’s Republic on February 9, 1918, elicited a harsh protest from the Regency Council. According to the treaty, the Holm Region and the southeastern part of Podlasie, i.e., the territories which the Poles considered “their own,” were ceded to Ukraine. The Regency Council called the treaty a “new partition” of Poland.

In the autumn of 1918, when the military defeat of the Central Powers was already evident, Polish politicians, dissatisfied with the passivity of the Regency Council, began to create local power structures. Several centers of power emerged in the Kingdom of Poland that did not interact with each other.

On October 6, 1918, the Regency Council demanded the creation of “an independent state encompassing all Polish lands with access to the sea, politically and economically independent.”

And in mid-October 1918 the Austro-Hungarian Empire, overstrained by the difficult situation at the front, crop failures, economic crisis, ethnic conflicts, separatist tendencies intensified after the collapse of the Russian Empire in February 1917, revolutionary sentiments, fueled by the success of the October Revolution in Russia, and so on, began the collapse.

On October 17, the Hungarian parliament declared the union with Austria terminated and declared Hungary independent.

On October 28 Czechoslovakia declared its independence.

On October 29, the State of Slovenes, Croats, and Serbs emerged.

On October 31, an armed uprising broke out in Budapest.

On November 3, the manifesto on the independence of Galicia and the establishment of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic (WUPR) was issued.

On November 6, the independence of Poland was proclaimed.

On November 11, 1918, Germany signed the armistice in Compiègne.

On the same day, November 11, the Kingdom of Poland was dissolved. The powers of the Regency Council were transferred to Józef Piłsudski, who at first created combat units that fought on the side of the Triple Alliance against Russia, and was even a member of the Provisional Council of State founded by the German administration in occupied Polish territory. But when the balance of power in the war was shifted to Germany’s disadvantage, Piłsudski turned against Germany and was even imprisoned by the Germans. This made Pilsudski a symbol of the struggle against the German occupiers and allowed him to return triumphantly to Poland after Germany capitulated.

On November 12, 1918, Emperor Charles I of the Austro-Hungarian Empire signed a certain document which, while not being an act of abdication, allowed the signatory monarch to make certain claims even after signing it, but nevertheless it de facto marked the end of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Thus, Germany and Austria-Hungary did not achieve their expected goals by the creation of the Kingdom of Poland. German plans to form the Polish armed forces were completely ruined. In addition, the proclamation of the Kingdom of Poland contributed to the development of the national movement in Galicia. And other peoples of Austria-Hungary, following this example, intensified their struggle for national self-determination.

We have described in sufficient detail the puppet Kingdom of Poland, created by the Germans and Austrians during World War I, because shortly after this, in 1918, amidst the Civil War, Austria-Hungary, living out its last months, tried to implement in Ukraine a similar, already proven model of semi-colonial kingdom. Only this time it was the son of Charles Stephen von Habsburg-Lothringen, Wilhelm von Habsburg-Lothringen, also known as Vasil Vyshyvaniy, who was offered the role of monarch.

Wilhelm von Habsburg-Lothringen and the Project “Ukrainian Monarchy”

Wilhelm von Habsburg-Lothringen, born in 1895 in Croatia, on an island in the Adriatic Sea where his father had a palace, lived from the age of 12 in the family castle in Western Galicia. Here he learned the Ukrainian language and became addicted to reading the works of Grushevsky, Shevchenko, and Franko. There is a version according to which Wilhelm was not satisfied with the future laurels of his elder brother Albrecht, who was predicted to be the king of Poland. And that Wilhelm had ambitious intentions to become the Ukrainian king at an early age.

This intention, however, did not prevent him from deviating from the Ukrainian trajectory for a while. In his book The Red Prince, dedicated to Wilhelm von Habsburg, Professor Timothy Snyder of Yale University cites an episode which he himself considers possible but unlikely:

“Wilhelm first identified with the Jews and only later with the Ukrainians. … Willy drew up a project for a state of Israel and approached the World Zionist Organization in Berlin to offer his services. One can imagine how he might have come to such an idea. Zionism, the idea of the return of the Jews to Palestine and the creation of a Jewish state, was gaining adherents. In 1913 the Third Zionist Cngress was held in Vienna, where Willy was living. Willy’s move to Vienna, in such scenario, would have been the crowning moment in his own discovery of a nation.”

Perhaps the youngest offspring of a cadet branch of the Habsburgs, who had virtually no chance at the throne, dreamed of becoming king of Israel. After all, his dreams were not entirely unfounded – the Habsburgs held the title of King of Jerusalem among other titles, even though the Kingdom of Jerusalem had long ago disappeared from the world map. But the Zionists showed no interest in the project proposed by the young Habsburg. And then he followed the “Ukrainian” path, donning a Ukrainian vyshyvanka [casual name for the embroidered shirt in Ukraine – translator’s note], which he wore under his military tunic.

In March 1915, Wilhelm Habsburg completed his training at the military academy and in June he was given command of a platoon in a regiment predominantly consisting of Galician Rusyns. Wilhelm demanded that his subordinates call him Vasil, spoke Ukrainian to the soldiers, and wore a vyshyvanka under his officer’s uniform.

After the Russian army’s counteroffensive in Galicia in the summer of 1916, Wilhelm was recalled from the front and temporarily sent to the rear, among other things to improve his health.

At the end of 1916, Charles I became emperor of Austria-Hungary, as previously mentioned. A good relationship was established between them.

On February 2, 1917, Wilhelm presented his “Ukrainian project” to Charles I. Wilhelm’s proposal was to turn Eastern Galicia into a Ukrainian principality (Ukrainian kingdom) after victory in the war. Wilhelm-Vasil saw a renewed Habsburg empire consisting of the kingdoms of Austria, Hungary, Poland, Bohemia, and Ukraine. He himself aspired to the role of monarch or at least regent of Galicia.

In July-August 1917, Wilhelm accompanied Emperor Charles I on a trip through Eastern Galicia.

A few weeks later, Charles I sent Wilhelm to Lvov to meet and establish connection with Andrey Sheptitskiy, head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Sheptitsky’s and Habsburg’s interests converged: both wanted the expansion of the Catholic faith to the east and both liked the idea of establishing a monarchy in Ukraine. A representative of the ancient Habsburg dynasty, who had come to Lvov in a vyshyvanka and who spoke Ukrainian fluently, was given a favorable welcome by Sheptitsky.

In a letter to Andrey Sheptitsky, Wilhelm wrote:

“His Majesty [Charles I] has been extremely kind to me and has instructed me to act in Ukraine not militarily, but politically. In this he gives me complete freedom, which to me is a proof of his trust. I believe that gradually I will be able to achieve everything that the brave Ukrainians desire…”.

When negotiations began in Brest-Litovsk at the end of January 1918 between Germany, Austria and the newly formed Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) on the conclusion of a separate peace, Wilhelm tried to actively influence the UPR representatives, convincing them that their negotiating position was stronger than it seems, thanks to the agricultural resources of Ukraine. Austria-Hungary was in dire straits at the time. The British naval blockade provoked a food crisis which prompted famine in the cities and in the army. During the days of negotiations in Vienna, 113,000 workers went on strike, demanding food.

On February 9, 1918, the Ukrainian Brest-Litovsk, or “bread”, peace was concluded, under the terms of which Germany and Austria-Hungary recognized the Ukrainian People’s Republic as a state. Under the terms of the treaty, the UPR was to supply a million tons of grain to Austria-Hungary by July 31, 1918, in exchange for military assistance. In a secret protocol, it was recorded that an independent Ukrainian province was planned to be created on the territory of Eastern Galicia and Bukovina.

Soon, the armies of Germany and Austria-Hungary occupied most of Ukraine. But there was no coherence between the Central Powers in their actions or plans. It took more than a month before they were able to agree on occupation zones. Germany got Kiev and the northern regions, the Habsburgs occupied the southern regions. Troops from both countries were stationed in Odessa. Two diplomatic missions were opened in Kiev.

Both Austria-Hungary and Germany, being in a difficult economic situation, sought before all to use Ukraine as a source of food and labor. At the same time, unlike Austria-Hungary, which quite consistently tried to implement a certain project in Ukraine related to the Habsburg prince, whom we are discussing, Germany was even more omnivorous in political terms. And it was ready to support a puppet government that could at least to some extent fulfill its indentured obligations to supply the Reich with what it desperately needed.

And since the Ukrainian Rada could not fulfill these obligations, at the end of April 1918 it was dissolved under the pressure of Germany. Pavel Skoropadsky, a protégé of Germany, was declared the hetman of Ukraine.

What about Austria-Hungary? Its protégé Wilhelm-Vasil Habsburg at that time headed the occupying Austro-Hungarian garrison of the city of Alexandrovsk (as Zaporozhie was then called). Under his command he had a four-thousand-strong detachment assembled by Emperor Charles I from Ukrainian soldiers of the Austrian army. This detachment included a special unit – the Legion of Sich Riflemen, which consisted mainly of Galicians and was engaged in intelligence and propaganda.

Wilhelm was well aware of how important it was to secure the Ukrainization of the population, so he approached this problem very seriously. He said: “There are only two possibilities: either the enemy will be able to expel me and engage in Russification, or I will stay and engage in Ukrainization.”

Wilhelm searched for and appointed Ukrainians to administrative positions, consistently and carried out propaganda of Ukrainism in the press, utilizing clever tactics. For example, he gained popularity among the peasants by preventing the seizure of food by the Austrian army. German military leaders reported on the “growing popularity of Archduke Wilhelm, known among the people as Prince Vasil.”

At some point, a Lieutenant Colonel from Skoropadsky’s army Petro Bolbochan (as a member of the Ukrainian Party of Socialist Independists, he did not feel any sympathy for Skoropadsky – Skoropadsky was for him both not left-wing enough and not “anti-Moskal”) came to Wilhelm. Declaring his support for the candidacy of Vasil Vishivanny for the Ukrainian throne, he invited Vasil to stage a coup and proclaim himself hetman of all Ukraine.

William reported the proposal to the Emperor of Austria-Hungary. In response, Charles I ordered to continue the policy of Ukrainization, but not to do anything that could undermine the alliance of Germany and Austria-Hungary or disrupt the supply of food.

According to the treaty, the UPR was supposed to deliver a million tons of food, but in fact not even a tenth of it was collected. Local gendarmes and police on the orders of the military burned villages that refused to hand over bread. Resistance grew, and more and more peasants met the collection of bread with retaliatory violence. The partisan movement, the anarchist and Bolshevik underground were gaining strength.

The German occupation forces were losing control of the situation. German intelligence reported that Vasil Vyshyvaniy was increasingly gaining popularity among the common people, and this threatened the current regime. Hetman Skoropadsky was furious. The German command disbanded the Legion of Sich Riflemen, but left a detachment of about 4,000 men for Vasil.

Despite the discontent of the Germans, Emperor Charles I sought to keep Wilhelm in Ukraine. For Charles, at that time, it was practically the only way to maintain Austrian influence in the region. He sent Wilhelm from the eastern front to the western front to speak personally with the German emperor.

The meeting between Vyshyvanniy and the German emperor took place on August 8, 1918, the day of a difficult battle for German troops on the western front. Wilhelm received a blessing from the German emperor. But the situation was rapidly deteriorating. And with such deterioration, the highest authority, losing the ability to pursue a definite policy on any issue, first approves one endeavor and then another, the exact opposite. Everything begins to depend on so-called “access to the body,” that is, on the ability of this or that aspirant to convince that “body,” access to which is obtained, of the value of his particular undertaking.

In September 1918 Hetman Skoropadsky himself went to German headquarters and obtained a promise that Wilhelm would leave Ukraine. At the same time, Charles I received a warning from the commander-in-chief of the Austrian forces in Ukraine that he could not guarantee Wilhelm’s safety in the current revolutionary situation.

On October 9, 1918, Wilhelm did leave Ukraine. The remnants of his detachment went to Lvov and joined the army of the West Ukrainian People’s Republic. Thus, the first Ukrainian monarchical project involving a representative of the Habsburg dynasty ended in failure.

Events in Ukraine developed rapidly. In December 1918 the Directory, headed by Petlyura and Vinnichenko, overthrew the Kiev government of Skoropadsky. On January 22, 1919, the UPR and WUPR created a single state with Kiev as its capital. Due to this unification, Wilhelm Vyshyvaniy became a colonel in the army of the UPR. However, the “independent, united Ukraine” did not last long: already on February 5, 1919, the Bolsheviks took full control over Kiev.

In September of that same year, Wilhelm, who by that time had already become head of the Foreign Relations Department of the UPR General Staff, found himself in Kamyanets-Podolskiy, the last stronghold of the Petlyura’s supporters. Here he takes part in the preparation of military units for the demoralized army of the adherents of the independent Ukraine.

In November 1919, the UPR army, pressed from three sides by the Bolsheviks, Poles and Whites [the military of the White Army – translator’s note], was surrounded. The army command decided to surrender to the Poles. Petlyura fled to Warsaw, where, in April 1920, he signed a peace treaty with the Poles. Under this treaty, the UPR ceded the territories of western Ukraine to Poland. Such a reckless distribution of “state” territories caused a violent protest from Wilhelm von Habsburg who then resigned and went to Vienna.

In early 1921, in an interview with a Viennese newspaper, Wilhelm criticized Poland, calling its military successes in Galicia “megalomania” and condemning the Polish army for the Jewish pogroms in Lvov . Wilhelm called the UPR’s alliance with Poland “unnatural” in the same interview.

Such an anti-Polish démarche was perceived by Wilhelm’s father, Charles Stephen von Habsburg, who was looking to ascend the Polish throne, as a betrayal. At the end of January 1921, Charles Stephen published an article in which he announced that all ties between Wilhelm and his family were henceforth severed. Because of this severance, Wilhelm was deprived of his sources of income.

Wilhelm assumed the role of a “Ukrainian” poet and publicist.

In 1921 Wilhelm published his collected poems in Ukrainian called Minayut Dni (The Days are passing by) under the pseudonym Vasil Vyshyvaniy.

In the same year of 1921, the newspaper Sobornaya Ukraina (United Ukraine) began its publication in the Ukrainian language in Vienna. Vyshyvaniy was one of its publishers. The emblem of the newspaper was the hammer and sickle, and the slogan was “Ukrainians of all countries, unite!” Vyshyvaniy argued in the newspaper that democracy could lead to monarchy and that a European state under a modern monarch would more reliably ensure democracy than a republic.

This is an obvious flirtation with Soviet symbols, reinterpreted in a Ukrainian-nationalist way. This flirting is complemented by the thesis that the transition from democracy to monarchy is possible and desirable. Of course, the 1920s was a time of the most exotic ideas. But let us assume that this idea is still alive today. In this case, according to this idea, a pan-European transition from the current EU democracy to some pan-European monarchy is also possible. And in the case of such a transition, the Habsburg dynasty is beyond competition. Because the real tradition of the formation of pan-European monarchy in more or less close historical periods is, of course, the tradition of the Habsburgs.

But let us return to the representative of this dynasty we are discussing.

In the 1930s, Wilhelm had contacts with the OUN – Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists – (organization banned in the Russian Federation) leader Yevgen (Ukrainina: Yevhen) Konovalets and his successor Andrey Melnik. Both Konovalets and Melnik had fought alongside Wilhelm in 1918. Now they used his communications to gain diplomatic support for Ukraine. Wilhelm even traveled to London on their errands. Wilhelm also met with the “spiritual father” of Ukrainian nationalism Dmitry Dontsov.

In June 1934, Hitler informed Mussolini that Wilhelm von Habsburg was a liaison between the Ukrainian nationalists and the Austrian volunteer military units. By “Austrian volunteer military units” he meant the Heimwehr, an Austrian nationalist paramilitary organization.

In 1935 a scandal broke out around Wilhelm, which was taken up and spread around by the French newspapers. The Austrian prince’s mistress, Paulette Couyba, had implicated him in fraud. Fleeing from prison, Wilhelm was forced to seek refuge in Austria. In France he was sentenced in absentia to five years in prison. Later Wilhelm, trying to clear his name, claimed that he had been framed by Czechoslovak intelligence.

However, soon the Order of the Golden Fleece, of which Wilhelm was a member (headed by Otto von Habsburg, head of the Habsburg-Lorraine house, the eldest son of Charles I, who had already died by then), began to study the circumstances of the Paris incident independently. As a result, Wilhelm von Habsburg voluntarily withdrew from the Order.

In Austria, Wilhelm was for a time a member of the Austrian fascist organization Fatherland Front. But later he separated from the Austrian fascists and became closer to the German Nazis.

In 1937, the Habsburgs regained great popularity in Austria. The Austro-Fascist government of Kurt Schuschnigg placed its bets on Otto von Habsburg, whom Hitler despised, seeing him as a rival for power. On Otto’s birthday, Vienna was decorated with black and yellow imperial flags.

Unlike Otto von Habsburg, Wilhelm opted for Hitlerism and even declared that the movement to restore the monarchy was doomed to failure because it was led by the Jew Friedrich von Wiesner. This surprised Wiesner, a longtime friend of the Habsburg family who had known Wilhelm personally for more than fifteen years.

In February 1937, Wilhelm met with his old acquaintance, also an admirer of National Socialism, Ivan Poltavets-Ostryanitsa. Poltavets-Ostryanitsa was Skoropadsky’s closest ally, who helped him to carry out the coup d’état and to establish the Hetmanate in 1918, and emigrated to Germany with him, after the fall of the Hetmanate. Poltavets-Ostryanitsa and Wilhelm discussed the re-establishment of the Ukrainian Legion as part of the Wehrmacht. The Ukrainian Legion was a kind of counterpart to the unit that had been under Wilhelm von Habsburg during World War I. As Wilhelm wrote in one of his letters, Poltavets-Ostryanitsa gave him the idea to contact Hans Frank (then Reichsleiter, the future Governor-General of occupied Poland), and he hoped to help the Germans recruit the Ukrainian Legion.

A few words should be said about Poltavets-Ostryanitsa.

In 1923 Poltavets-Ostryanitsa created the Ukrainian People’s Cossack Society (UNAKOTO), whose ideology from the very beginning was National Socialism. “The Society was formed as a military-political organization that aligned itself with the program and goals of National Socialism and Fascism,” Poltavets-Ostryanitsa wrote in a letter dated April 10, 1923, to Adolf Hitler. This letter provides a detailed breakdown of the Ukrainian emigre forces in Eastern Europe. The author also asked the future Führer for “financial and moral assistance.” He suggested that the NSDAP convene, as a counterbalance to the International, a “first National,” that is, an international union of National Socialists.

Ostryanitsa managed to establish friendly relations with Hitler. For example, on April 20, 1923, he sent Hitler a letter congratulating him on his birthday and expressing “the hope that the day is near when all nationally conscious peoples will achieve victory over the International.”

At the same time, in the early 1920s, Ostryanitsa met and established friendly relations with Alfred Rosenberg, another leader of the NSDAP.

Poltavets-Ostryanitsa publishes the newspaper Ukrainian Cossack in Munich. The issue of March 1, 1923 proclaimed:

“We believe that any of our humblest personal desires should be set aside, and in their place should be:

- Nationalism

- National socialism

- Cossacks as self-defense forces of the nation.

- Deft diplomacy, understanding contemporary tactics, which is covered by one word: dictatorship, and the dominance of the national people’s party until the state is established, until it can show its real will without a democracy mutilated by the revolution and the Jewish minority.”

The UNAKOTO charter of 1923 stated that “only a Cossack can be” a citizen of the Ukrainian State, “and only a Ukrainian by blood regardless of religion can be a Cossack.” Foreigners were forbidden to take part in the ruling of the Ukrainian State. Hetman Fascism of Ostryanitsa, following German Nazism, professed anti-Semitism, “Jews cannot be citizens of the Ukrainian State at all,” the same charter stated.

On July 1, 1926, shortly after Petlyura’s death, Poltavets issued the 1st Ukrainian Universal, in which he declared himself “Hetman and National Chief of all Ukraine on both sides of the Dnepr and of the Cossack and Zaporozhye armies.”

The Cossacks were attracted to the ideas of integral nationalism, and therefore in the 1930s the UNAKOTO included many members of the OUN (organization banned in the Russian Federation). Poltavets-Ostryanitsa claimed that UNAKOTO had eight camps – (in Bulgaria, Romania, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and even Morocco).

In 1935 UNAKOTO was transformed into the Ukrainian National Cossack Movement (UNAKOR). The charter of the UNAKOR proclaimed the construction of “a new specific Ukrainian-Cossack national-socialist fascist way of life of the people” as its goal.

On May 23, 1935, Poltavets-Ostryanitsa officially addressed Hitler with the following words, “By this act I place at your disposal all armed and combat-ready representatives of the Ukrainian Cossacks, who are in Germany and abroad.” But Hitler and his entourage did not take this proposal seriously. In the Gestapo reports it was stated that the UNAKOR existed “only on paper and practically had no supporters.”

As we can see, Wilhelm von Habsburg was interested in the possibility of cooperation with the Third Reich and was looking for some important role for himself in Hitler’s project. However, discussions between him and Poltavets-Ostryanitsa about the prospect of recreating the “Ukrainian Legion” did not go beyond that.

After the fall of Poland in 1939, Karl Albrecht, Wilhelm’s older brother, who had lived in Poland all his life, found himself in occupied territory. On his first visit to the Gestapo, he stated that he considered himself a Pole and had raised his children as Poles. At the same time, he did not deny that he was of “German descent” because his ancestors had been Holy Roman Emperors of the German Nation for hundreds of years. Gestapo officers concluded that Karl Albrecht’s entire life “has been a complete betrayal of Germaneness, and this alone excludes him from the German community once and for all. His treason can never be atoned for, and therefore he has lost all right to his property and all right to live in Germany, even as a foreigner.” Albrecht and his wife were placed in a labor camp. After being tortured by the Gestapo, Karl Albrecht was half paralyzed and blind in one eye.

In 1940, Wilhelm was drafted as an officer into the German army. But he was not enthusiastic. Although sympathetic to the Nazis, he was not a member of the NSDAP. He was 45 years old, but he had been suffering from tuberculosis and heart problems for many years. Instead of regular service in the Wehrmacht, he was relegated to the rear to carry out defense tasks.

Realizing that the Germans did not see him as a player on the Ukrainian field and that his big political plans for a second attempt at a Ukrainian monarchy had to be abandoned, Wilhelm went to Germany to visit his older sister Eleonora. Eleanora married a simple German officer and bore him eight children. Six of her sons served in the Wehrmacht.

Wilhelm and Eleanora sued to reclaim their brother’s property seized in Poland or to be compensated for it. The court took into account that Eleanora and Wilhelm were German by blood and culture, and that Eleanora had eight German children, and awarded both of them compensation. Wilhelm received 300,000 marks and Eleanor received 875,000 marks. These amounts correspond to the current $9 million and $27 million.

In 1942, Wilhelm met a young man named Roman Novosad in a café. Novosad, a native of Galicia, was studying at the Vienna Conservatory. When he heard him speaking Ukrainian with his friend, Wilhelm introduced himself, “I am Vasil Vyshyvaniy.”

Novosad was a UPA – Ukrainian Insurgent Army – (organization banned in the Russian Federation) liaison, and by that time Vyshyvaniy, disappointed in the German Nazis who rejected him, had reoriented himself toward the Allies and began working for the French and British intelligence services. Vyshyvaniy was one of those who forged the links between the Allies and the UPA (organization banned in the Russian Federation), which allowed the Ukrainian Nazis to be taken under the wing of Western intelligence after the defeat of Hitler.

By becoming an important element in the system for ensuring such a reorientation As an important element of the system that accomplished this reorientation of the Ukrainian Nazis, Wilhelm strengthened his authority in the Western security services and became one of the curators of the Banderites who changed their coat in the postwar period. Wilhelm was one of the creators of the Ukrainian nationalists and collaborators’ network of agents in Eastern Europe.

One of Wilhelm’s charges was Ukrainian Nazi Vasily Kachorovsky who had also changed his coat. With Wilhelm’s help, Kachorovsky began working for French intelligence. SMERSH officers captured him in 1947, and he gave up information about Roman Novosad and Wilhelm von Habsburg. Novosad was taken next and gave up Wilhelm’s whereabouts. On August 19, 1947, Novosad was arrested, the next day Wilhelm was arrested. Major Goncharuk was in charge of the operation.

On May 29, 1948, Wilhelm was sentenced to 25 years. On August 18, he died in the Kiev prison hospital of tuberculosis.

But the death of this particular member of the Habsburg dynasty did not stop the Habsburg family from flirting with Ukraine.

Source (for copy): https://eu.eot.su/2022/06/27/the-habsburg-in-a-vyshyvanka-ukrainism-chapter-iv/

This is the translation of Chapter IV of the multi-authored monograph “Ukrainism: Who constructed it and why” first published in 2017 and re-published on the Rossa Primavera News Agency‘s web-site on March 6, 2022. This research work was written by the members of Aleksandrovskoye commune, which is part of the School of Higher Meanings of the Essence of Time movement and is supported by the members of the Experimental Creative Centre International Public Foundation.

Dr. Sergey Kurginyan is a political and social leader of the Essence of Time movement, theater director, philosopher, political scientist, and head of the Experimental Creative Centre International Public Foundation.

Speaking about the topic of the monograph “Ukrainism: Who constructed it and why”, Sergey Kurginyan explained, “We are studying Ukrainism, not Ukraine. Our subject is Ukrainism as a construct. The creation of this construct, its characteristics, its consecutive transformation, its implementation, and finally its outlook―this is the focus of our study, which is thus fundamentally different from a normal historical or sociological study of a normal Ukraine”.