In 1920, amidst the civil war, the Soviet government started implementing the GOELRO program (the first of Soviet Russia’s plans for national economic recovery and development), marking its aspiration for the future. The Luna-25 mission is a much more modest event but also outlines the contours of the future

After a break of almost 50 years, Russia has returned to lunar exploration. And this happened in the context of the ongoing and increasingly demanding Special Military Operation to denazify and demilitarize Ukraine.

On August 16, the Russian automatic station Luna-25 entered the orbit of the Earth’s satellite. This can already be considered a partial success of the mission: Russia now has a basic module for creating an automatic interplanetary station and an orbital station. However, the main thing – landing on the surface of the Moon – is still ahead.

The Soyuz 2.1b rocket launched from the Vostochny Cosmodrome on August 11 at 2 hours and 11 minutes. According to the plan, the landing on the Moon will take place on August 21 near the South Pole.

The expedition is of high scientific significance. First and foremost, it will be the first landing in history in the area of the South Pole of the Moon, where, as it is assumed, there are large reserves of water, which is extremely important for any projects of lunar exploration and creation of a lunar base. Secondly, it is the start of the Russian program of human landing on the Moon.

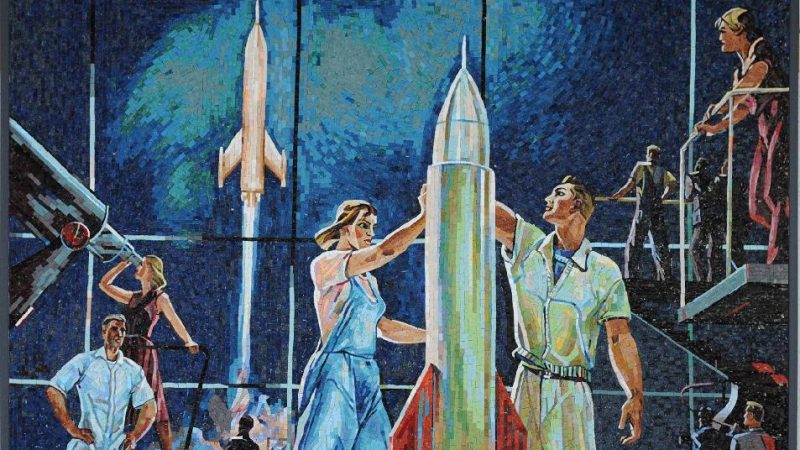

The implementation of such an ambitious program in the current military and political situation reminds us of the history of the beginning of the Soviet government’s grandiose plan to transform the country’s economy on the basis of electrification of the national economy GOELRO. The project was launched in the midst of the civil war.

Of course, the scale of the program is different, but there are similarities between the two projects. Russia today, like the USSR at the beginning of the 20th century, does not focus on today’s events but invests efforts and resources in a distant and seemingly today poorly discernible prospect.

From this point of view, it is interesting to look at the reaction that the Luna-25 mission caused in Russia’s adversaries.

Western media began commenting on the mission in light of the anti-Russian sanctions imposed since the beginning of the Special Military Operation.

“There is much riding on the Luna-25 mission for Russia: if it succeeds, Russia is likely to say it shows that the West’s sanctions over the Ukraine war cannot hold Russia back,” Reuters writes.

The New York Times expressed itself in a similar spirit, “It’s a test that will be keenly watched around the world as Europe and America work to isolate Russia amid the war in Ukraine, and as Russia tries to strengthen its political and economic ties with non-Western countries in response. Mr. Putin sees Russia’s space program as one prong of that effort.”

As polls show, the giant efforts to strangle Russia economically have not been as crushing as Western countries had hoped. If, against this background, the sanctions do not seriously impact Russia’s technological capabilities, the very concept of fighting Russia on the economic field, which, incidentally, is very costly for Europe, fades to a certain extent.

The topic of the impact of sanctions on the Russian lunar program was touched upon in a large interview published on the website of Roscosmos, Executive Director for Advanced Programs and Science of the State Corporation Roscosmos Aleksandr Bloshenko, “Of all industries, we were probably the most prepared for sanctions – we have lived in this situation for many years. It has not affected Luna-26 and Luna-27 in any way. The only thing is that we have always tried to do such projects with international partnerships. If our foreign colleagues suddenly change their plans, we will supply purely Russian-made equipment together with the Russian Academy of Sciences”.

NASA’s head Bill Nelson saw the launch of Luna-25 as an occasion to speak on the subject of the space race. Congratulating his Russian colleagues on the successful launch of the mission and wishing it good luck, Nelson said. “I don’t think that a lot of people at this point would say that Russia is actually ready to be landing cosmonauts on the moon in the time frame that we’re talking about. I think the space race is really between us and China.”

In the sense that Nelson puts into words “space race”, i.e. 2025 for the US lunar program and until 2030 for the Chinese one, Russia is really unlikely to meet the deadline.

Regarding Russian plans to land on the Moon, Aleksandr Bloshenko himself noted, “A Russian flight to the Moon is not a matter of the near future. It may happen after 2030. It will depend on the creation of means of delivery: a manned transportation complex, a lunar takeoff and landing vehicle, a super-heavy-class launch vehicle, as well as on the development of our cooperation on the creation of the International Scientific Lunar Station.”

However, if we are not talking about planting a flag, but about the beginning of systematic development of the Moon for national and economic purposes, Russia’s programs do not look so bad. Russia doesn’t have a superheavy carrier for a lunar expedition, but no one else has one yet. The US Starship SuperHeavy has not even made a suborbital flight yet.

The permanent presence on the Moon needs energy. And it must be supplied not only from solar batteries. Thus, Aleksandr Bloshenko explained, “Russia is currently developing an interorbital transportation module using a gas-cooled nuclear reactor and a turbomachine system for converting thermal energy into electrical energy with a capacity of up to 500 kW. The main components of its power plant are made according to the modular principle and can be used for the creation of a nuclear power plant on-planet, including lunar. Besides, we will need such an interorbital nuclear propulsion spacecraft for transport and cargo support of the lunar base – it will be able to deliver tens of tons of cargo to the Moon”.

Let me explain, we are talking about the Zevs nuclear propulsion spacecraft, the development of which is covered by a veil of secrecy, but from time to time, this or that information gets into the media. I should note that only recently, a competition for the development of such a nuclear propulsion spacecraft was announced in the USA. In other words, Russia may have an ace up its sleeve in the real lunar race, the prize of which will be a lunar base.

The meaning of the words “space race” is similarly understood by some Western experts. What really matters, going forward, is who is able to set up a sustained and worthwhile presence on the moon, argues Vishnu Reddy, professor of planetary sciences at the University of Arizona.

“Competitions only take you to the flag. You can’t have sustainable, long-term presence based on politics or trying to beat one nation or the other,” the BBC quoted the scientist as saying.

The scientific director of the first stage of the Russian lunar program, Academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences Lev Zeleny commented on what is a “sustainable, long-term presence” on the Moon shortly before the start of the mission. He said, “One of the reasons for today’s interest in the Moon is the possible extraction of lunar resources, first of all, rare earth metals associated with metallic meteorites that collided with the Moon during its evolution. And secondly, water ice reserves at the poles.”

In the same days also in the area of the South Pole of the Moon is scheduled to land station Indian mission Chandrayaan 3. According to the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), the separation of the landing module is scheduled for August 17.

The Western media, captive to the paradigm of continuous competition of everything and anything at once, started talking about a lunar mini-race between Russia and India. Although in this case, it is more about cooperation between the countries in space exploration. For example, an Indian launch vehicle was shortly before being considered as a carrier for Luna-25, as Lev Zeleny mentioned, “Initially, Luna-25 was to be launched together with the second Indian lunar lander Chandrayaan 2 on an Indian carrier rocket.”

And the Indian lunar rover, which is part of the Chandrayaan 3 mission, was planned as part of the scientific equipment for Luna-25.” India’s South Pole Moon exploration program is also aimed at finding water, but unlike Russia’s Luna-25, which is supposed to operate on the Moon for a year, the Chandrayaan 3 landing module is scheduled to operate for 14 days.

The implementation of the Russian lunar program, launched amidst ongoing Special Military Operation, is not only the implementation of scientific projects. The lunar program implemented under the conditions of the Special Military Operation is a step of Russia away from the Western “track” of development, as Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said, to its own historical path, which has been once abandoned.

This is a translation of the article by Sergey Bobrov, first published by Rossa Primavera News Agency.