(Links to previous Chapters are available here: Preface)

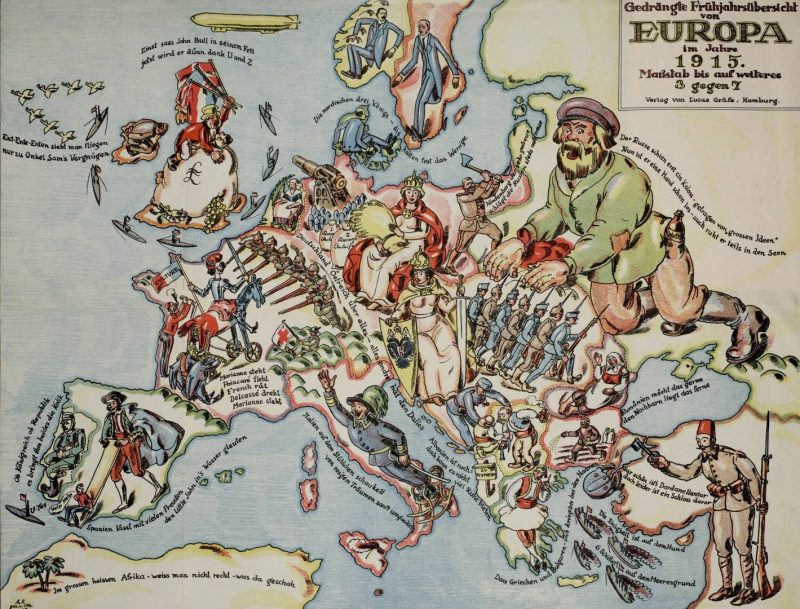

Today is not the first time that Ukraine is regarded as a buffer or a possible foothold for an invasion of Russia. During the last century the country most active in this respect was Germany.

On November 21, 2013, protests were ignited by then Ukrainian leader Viktor Yanukovich’s government’s decision to pause Association talks with the EU. These mass protests centered around the capital city of Kiev.

Unrest quickly escalated into months long civil action and protests, these quickly became labeled by local and international news outlets as the “Euromaidan.” As we know today, Euromaidan grew into an unconstitutional coup, resulting in the secession of the Crimean Peninsula from Ukraine and a bloody civil war in the Eastern regions of the country.

We focus here on the part played by one of Ukraine’s major European patrons — Germany.

In early December, 2013, Germany’s foreign minister Guido Westerwelle visited the Euromaidan. Following the visit the Ministry stressed on its web-site, “We do care about the destiny of Ukraine … This shows that the heart of the people in Ukraine beats for Europe.”

In addition to political support, Germany promised to back Kiev financially. On February 17, 2014 Berlin held a meeting with the coup leaders Arseniy Yatsenyuk and Vitaly Klichko who convened directly with Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel. Immediately after this gathering, Yatsenyuk told journalists that Ukraine would be forming a new government “which will be given support from our western partners in order to stabilize the financial situation in the country.”

Germany was not the only western country to throw its financial and political support behind Kiev, with the USA willing to go as far as e providing military and technical assistance.

Why was the West so eager to help Ukraine? First and foremost, it had to do with the view – held by many western politicians and strategists – of the former Soviet state as a buffer zone between Russia and Europe. As a country that could become a “cordon sanitaire”. George Friedman, the head of the US-based private intelligence/analytical agency Stratfor, told the Kommersant newspaper in an interview on December 19, 2014:

“The US will need to make a strategic decision, not now but in the future, either to intervene more actively in events in Ukraine, which is fraught with difficulties, or to build a new alliance — within NATO or outside of NATO — with the participation of Poland, Romania, the Baltic States and, for example, Turkey. This is already happening, slowly but it is happening. And this will be something that Russia will not accept — a “cordon sanitaire.” It’s not that the US needs to have control over Ukraine; for them the important thing is that it not be controlled by Russia.”

Today is not the first time, when Ukraine is regarded as a buffer or a potential launching point for an invasion against Russia. Historically, it was Germany that has shown the most zeal in this direction during the past century.

The state of affairs seen by the late 19th century is telling: German society was then split into two major political camps.

One sought to continue a Bismarkian policy that viewed Russia as an equal partner.

The other saw Russia as an adversary and firmly believed that Germany had to expand by annexing Russian territories. The debate here centered around what territories to seize and how to govern them once control was established.

Members of Pan-German League, an organization founded in 1891 to defend German colonial interests, held the most aggressively anti-Russian views. That league emerged from the Heligoland–Zanzibar Treaty which was an agreement signed on July 1st, 1890 between the German Empire and the United Kingdom which aimed to delimit spheres of influence in East and South-West Africa. Its members decried the Bismark government for what they perceived to be giving too many concessions to England in the division of spheres of influence in Africa. The group fervently called for German global dominance, harboring designs to defeat the Russian Empire and seize its lands up to the Ural Mountains. They saw Ukraine as a foothold for an invasion to the East and Ukrainian nationalist movement as a tool to destabilize Russia. As part of this plan any independent government – even a puppet one – of Ukraine was out of the question. The league, whose members would later join the fascist movement, sought a direct occupation of Ukraine.

On the other hand, the less aggressively minded part of the anti-Russian group consisted primarily of representatives of the German Foreign Ministry and figures from the Kaiser’s entourage. This group promoted the idea of dismembering Russia by creating independent states carved out of its own territory. Ukraine was seen by members of this group as a cordon sanitaire designed to counter Russia’s expansion to the West. Two of the most well known proponents of these ideas were publicists Paul Rohrbach, and his friend and colleague Axel Schmidt. These figures warrant closer examination.

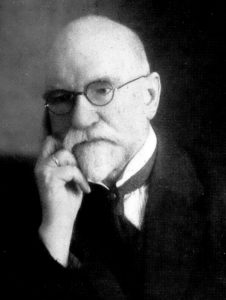

Paul Rohrbach was a renowned German political writer in the beginning of the 20th century. He is the author of more than 2500 publications devoted mainly to the development of Germany. In his publications, Rohrbach developed the idea of the superiority of German culture over other cultures and its important role in the special destiny of Germany itself. It was Rohrbach who formulated the idea of creating states in the western territories of Russia, independent de jure but fully controlled by Berlin.

Rohrbach considered Russia’s defeat in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 to be the proof of Russia’s weakness. On the eve of World War I, he was one of the leading experts on the “Russian question”, and in this capacity he was an advisor to the German Army and Foreign Ministry. Beginning in 1918, Rohrbach was actively engaged in the topic of Ukrainian independence. In particular, he insisted that Ukraine and the Ukrainian people cannot be the subject of Russia’s domestic policy, but must instead become an international issue.

Axel Schmidt, a close friend and collaborator of Rohrbach, was, at different times, the editor of the magazines “German Politics”, “Ukraine” and “German Thought.”. Together with Rohrbach, he created the German-Ukrainian Society in Berlin in 1918. He was one of the experts on ethnic issues in Russia and advised the German government during the anti-Russian propaganda campaign He was an ardent supporter of German imperial expansionism.

Almost a month after the outbreak of World War I, Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg declared that “the main purpose of the war” was “to ensure the security of the German Empire in the West and the East for all time.” In his program, he pointed out that it would be necessary “to push Russia away from the German border as far as possible and undermine its domination over non-Russian vassal states and their peoples.”

On September 9, 1914, Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg wrote a note to Secretary of the Reich Interior, Clemens von Delbroke, “On the Guiding Lines of Policy in Making Peace,” in which he outlined the ideas born among German industrialists and financiers. In particular, von Bethmann-Hollweg declared the thesis of the construction of Central Europe (Mitteleuropa), in which Germany would achieve dominance over France, Belgium, Holland, Austria-Hungary, Poland and, if possible, other countries. It was also to create a belt of “buffer states” around and at the expense of Russia.

The implementation of the “main objective” of “ensuring the security of the German Empire in the East”, declared by the Reich Chancellor, began long before the outbreak of the war.

In 1912, the Polish newspaper Słowo reported on the financing by the German embassy in Vienna of the magazine Ukrainische Rundschau, which was in charge of the active anti-Russian propaganda: “The newspaper knows that between the German embassy in Vienna and Ukrainian agents… there is a connection not only spiritual, but also material, in other words, financial; the intermediary is not the ambassador himself, but the embassy counselor Dietrich von Bethmann-Hollweg, a cousin of the chancellor.”

Concerning the German consulate in Lvov, Słowo wrote that it “deals mainly with Ukrainian affairs in Russia. On Ukrainian affairs in Austria, Berlin, in addition to direct relations with its Ukrainian clerics, influences through diplomatic pressure on the Austrian government.”

In addition, Germany gave its attention to the nationalist movement fostered by Austria-Hungary in Ukrainian Galicia and Bukovina. The policy of the Habsburgs there served Germany’s interest entirely. The Austrians closed Russian schools and boarding schools, Orthodox churches and chapels, and banned Orthodox services. Ukrainian nationalist movements and organizations received political and financial support leading to Ukrainian nationalist leaders to emphasize their loyalty to the Austrian and German governments. This loyalty immediately called into question all of their exclamations about Ukrainian independence.

One of these Ukrainian nationalists, Dmitry Dontsov, declared in 1913 at the Second All-Ukrainian Student Congress held in Lvov that those who would not side with Austria and Germany in the future war against Russia would be considered criminals to their nation. Dontsov argued that the slogan “independence” was no longer relevant. He called for a new, more relevant, real, concrete, and achievable slogan of “breakaway from Russia”, severing any ties and for complete political separatism. Because of the objective processes, he argued, any defeat of Russia, any separation of even a piece of Ukrainian territory in favor of Austria would lead to consolidation, to the strengthening of the Ukrainian element in Austria, and therefore in Russia, and would bring closer the time of the final liberation of Ukraine.

At the end of July 1914, a secret meeting of the highest officials was held in Vienna. Participants in the meeting requested Metropolitan Andrey Sheptitsky of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, one of the meeting participants, “to prepare instructions to the Austrian and German Governments for their future policies in Ukraine in the event of the dissolution of Russia.”

The analogy with the current situation is obvious. Euromaidan leaders do not hide the fact that their ideological roots go back to Dontsov and Sheptitsky. Arseniy Yatsenyuk (who was prime minister of Ukraine from 2014 to 2016) praised Sheptitsky’s works in his 2010 article and spoke about building the state according to his models, “It is no accident that the Metropolitan chooses the Khata [small peasant house in Ukraine – translator’s note] as a model for the state,” Yatsenyuk wrote of Sheptitsky’s book How to Build a One’s Own Khata, which can only be built with a well-thought-out project and “possessing sufficient knowledge.”

The November 2013 riots in Kiev were preceded by long preparations according to a prearranged plan. George Friedman admitted in June 2014, “For them [for Moscow – R. V.], the Western claims of a popular rising in Ukraine are belied by the Western-funded nongovernmental organizations that were critical to sustaining the movement to unseat the government.”

Returning to the events of the early twentieth century, it is important to emphasize that the Ukrainian Nationalists openly welcomed the outbreak of World War I in hopes that Germany and Austria-Hungary would win. In Lvov, Representatives of the Ukrainian National Democratic, Radical and Social Democratic parties united to form the Supreme Rada of Ukraine (SRU) (Supreme Ukrainian Council), which was headed by Kost Levitsky, a prominent member of the pro-German Union for the Liberation of Ukraine. As a result of the February Revolution in Russia the monarchy was overthrown and shortly after political parties and social movements in Ukraine decided to take power into their own hands, creating the Central Rada (Central Council of Ukraine) in Kiev.

After the Great October Socialist Revolution, the Central Rada declared the establishment of the Ukrainian People’s Republic (UPR) as a federal entity within Russia. This was followed by a declaration by the Rada on January 22, 1918, that the UPR was an independent state. With its new found independence a delegation of the Central Rada signed a separate peace treaty with representatives of the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, Turkey and Bulgaria) on February 9, 1918 in Brest-Litovsk,

The Central Powers recognized the sovereignty of the UPR and made a commitment to support it militarily. In exchange, the new Ukrainian government was obliged to supply them with foodstuffs and raw materials. As soon as in March 1918, at the request of the UPR representatives, German troops entered Kiev.

Now, almost a century later, a similar situation has developed. Ukraine has signed an association agreement with the EU, which, according to experts, allows its “Western partners” to plunder the Ukrainian economy. Foreign military instructors are in Ukraine, and reforms are being carried out by foreign officials who have adopted Ukrainian citizenship for the purpose to work in the Ukrainian government. The only thing missing so far is a direct military occupation of the country.

What was the outcome of this policy at the beginning of the 20th century?

The correspondence of German and Austro-Hungarian ambassadors and military representatives to Ukraine provides a complete picture of the dynamics of events. A state publishing house published this correspondence in 1936.

From the documents being part of this correspondence, it is immediately evident that the independence of Ukraine was purely nominal. “Moreover, the main purpose of our occupation,” the German Foreign Ministry instructed its ambassador to Kiev on March 26, 1918, “is to secure the export of grain from Ukraine to countries of the Central Powers … The government of the Rada must be continuously reminded that we are fulfilling its request and are strengthening its position, but that we demand that all measures possible be taken to secure the export of grain.”

Today Germany’s most demanded commodity is not grain, but oil and gas. But its approach to meeting its needs is the same as it was a hundred years ago. And this is evident even in a superficial comparison.

On 8 September 2014, Poroshenko reformed the management system of Ukraine’s gas transport industry. This reform gave legal entities “owned and controlled by residents of the European Union, the United States or the European Energy Community” the rights to manage the gas transportation network.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the new government in Ukraine was unable to provide the necessary volume of grain exports to Europe on its own. The German Foreign Ministry instructed its ambassador in Kiev on March 26, 1918, “We are far from desiring to interfere in the internal affairs of the Ukraine. We must see, however, that cultivation of the fields is carried out fully; if necessary, some of our regulations can be sacrificed…”

Soon the situation worsened to such an extent that the German military proposed to take it under their direct control. The Chief of Staff of the Army Group Kiev General Wilhelm Groener in his letter of March 31, 1918 to the German Ambassador to Kiev, Philipp Alfons Mumm von Schwarzenstein, notes, “Judging by the impressions our commanders developed <…> although the government implements the measures we desire, in the countryside no one thinks of carrying out its orders.” And he suggests, “In areas where there are a sufficient number of our occupation troops, we should try in the near future to bring our commissioners into contact with producers through local merchants.”

On April 3, 1918 the Austro-Hungarian ambassador to Kiev, Count János Forgách received a similar recommendation in a coded telegram, “Lieutenant-Field Marshal Langer reports that he firmly believes in the possibility of obtaining a significant amount of food from Ukraine on the condition that: 1) if the Ukrainian government was replaced by another, which would not offer passive resistance, 2) a sufficient number of troops would arrive in the country, and 3) sufficient energy and ruthlessness would be shown in procuring food supplies.” In the same telegram, the Foreign Ministry of Austria-Hungary promises that “four to five divisions must arrive in Ukraine” because “Austria is unable to withstand until the new harvest; unless at least fifty thousand train cars arrive before the new harvest, which Lieutenant-Field Marshal Langer says can be obtained, disaster will be inevitable.”

On April 5, the German Foreign Ministry sends Mumm a report from the German military plenipotentiary in Kiev, which states:

“The Ukrainian government was at one time a suitable instrument for concluding a peace treaty, but at the moment its power does not extend beyond the power of our bayonets. The government is afraid to export grain out of the country at all, let alone the quantity stipulated by the peace treaty… this government can only be worked with if we force it to act and organize as we order.”

By this time Germany’s position in the war was already becoming very difficult. The large-scale spring offensive on the western front required enormous resources and did not permit the use of military force for permanent control of Ukraine. On April 5, Mumm asked the German Foreign Ministry to send Paul Rohrbach to Kiev in order to apply other methods, “I think that the indirect influence of a well-known friend of the Ukrainian idea, Rohrbach, would be more useful than direct influence through the embassy or military, which would be perceived as violence.”

Meanwhile, major Ukrainian landlords themselves began to demand the use of military force. The peasants, who had received their land from the Central Rada of the UPR, did not want to give it back to their former owners. The landlords had been persuading the German and Austro-Hungarian governments that the peasants, having seized the landed estates of the landlords, would not be able to work the land, that the crops would be lost, and that this would lead to famine and unrest. At the end of April 1918, Count Grocholski, a representative of the delegation of Polish landowners in Warsaw, appealed to the Austro-Hungarian diplomat Gabor Ugron requesting urgent help and suggested his calculations, according to which “order could be restored easily if in every district there were about 1,000 soldiers in close columns (with machine guns). Since there are 36 counties on the right bank of the Dnepr, 36,000 men would be sufficient for this purpose.”

Soft measures and Paul Rohrbach being asked to help didn’t lead to the expected outcome. On April 18, 1918, Mumm coordinated plans to replace the Ukrainian government with his superiors: “The reason for replacing the government can be the peasant’s protest against the agrarian policy of the government appointed on April 15 according to the old calendar.” Before replacing the Central Rada government, Germans decided to make it assume responsibility for signing a new, even more devastating agreement for Ukraine, on shipments of bread and foodstuffs to Germany. The agreement was signed on April 23, 1918.

On the night of April 24-25th in Kiev, the banker Abram Dobryi, whose bank acted as an intermediary for financial transactions between the occupation troops and the Reichsbank, was kidnapped. This event acted as a trigger.

On April 25, 1918, Field Marshal von Eichhorn, commander of the German troops in Ukraine, issued an order to military field courts. According to the order, persons found guilty of violating public orders, committing criminal offenses and partaking in crimes against German and allied troops on the territory of Ukraine “shall be tried by German court-martial.”

The German command announced that Minister of Internal Affairs Mikhail Tkachenko, Minister of War Aleksandr Zhukovsky, and Prime Minister Vsevolod Golubovich had arranged the banker’s kidnapping. On April 28th, German troops dissolved the Central Rada and issued an order for the establishment of courts-martial. On April 29, Pavel Skoropadsky was proclaimed hetman of Ukraine at the first meeting of the All-Ukrainian Congress of Grain Growers in Kiev.

On May 2, Mumm wrote that “the only respected authority in the country at present standing behind the back of the new government … is the German Supreme Command.” On the kidnapping of the banker Mumm wrote that “the immediate pretext of these events was rather insignificant.”

Among Eichhorn’s headquarters staff, the personality of Hetman Skoropadsky was assessed positively stating that the hetman “is clearly aware that it is possible to restore the normal level of the country’s economy only under the condition of complete orientation on Germany.” Of the local authorities, however, it is written that

“it will not be difficult for German troops to maintain order and peace if we finally abandon the fiction of being present in a friendly country … in which we must ask permission for our actions from the feckless or untidy Ukrainian commissars and commandants … to force the bread supply will be possible only by eliminating the troublesome elements in the countryside.”

The Deputy Foreign Minister Baron von dem Bussche-Haddenhausen asked Mumm for a more precise explanation of the meaning of the phrase, “First, we must give up the policy which appears to convey the fiction that we are simply present in a friendly country.” “Does this mean,” Baron asks, “that we must not treat the Ukraine as a [free] nation at peace with us, but simply as a region of occupation?”

Mumm responded by explaining that in relations between Germany and Ukraine it is necessary to support “the fiction of an independent state friendly to us …”. He adds that this is necessary to avoid criticism from international public opinion and a negative reaction from the Ukrainian population.

On May 22, 1918 Eichhorn issued an order to the Eastern Army in which he listed the conditions accepted by Hetman Skoropadsky necessary for Germany’s support of his government. Among these are the obligation to fulfill the Brest agreements and the obligation to introduce court proceedings on the territory of Ukraine based on German courts-martial. If the incidents are not governed by Ukrainian laws, German laws must play the decisive role.

Skoropadsky’s government reinstated the rights of major landowners. The small and landless peasantry, who had already received some land, began to resist the seizure of their land by the landlords. The authorities roughly suppressed the riots, but Ukrainian troops couldn’t manage to fully accomplish the pascification. In June 1918 Skoropadsky’s government requested foreign support. On June 21, Foreign Minister Doroshenko wrote a letter to the German ambassador in Kiev, saying that “There are German troops only in certain areas,” and asking that they should be “spread out over all districts to help Ukrainian institutions.”

With the Germans’ defeat in WWI now inevitable they were unable to meet any of the Ukrainian’s requests for assistance.

On November 11, a German delegation led by Major General Detlof von Winterfeld met in a railway carriage with French Marshal Ferdinand Foch and signed the Compiègne armistice, acknowledging Germany’s defeat in World War I.

On December 14, 1918 Hetman Skoropadsky signed his abdication and fled to Germany, where he continued his anti-Soviet activities. On April 16, 1945, he was seriously wounded during the Allied bombing raid on a railway station in Plattling near Munich, and he died 10 days later in the hospital in the Bavarian town of Metten.

The Treaty of Versailles of 1919 drove Germany in a dire straits. Under the treaty, Germany was effectively left without a modern industry. It was forbidden to have a large army (no more than 100,000 men, including no more than 4,000 officers), a general staff and a submarine fleet. In addition, it was deprived of colonies and had to pay huge reparations to the victors.

In such circumstances, the most suitable trading partner for Germany was Soviet Russia, which at that time was in political and economic isolation. The country had set a course for rapid industrialization, had reserves of raw materials, minerals and the ability to export food.

At the same time, the Soviets experienced an acute shortage of new technology, machine tools, and highly skilled personnel – which, in turn, Germany possessed.

Despite the obvious advantages for both sides, the German elite did not have a unified position regarding cooperation with the young Soviet state. Even before the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, Rudolf Nadolny, the German Foreign Ministry’s eastern affairs adviser, formulated the dilemma that would determine Germany’s future path as follows:

either “to unite with the Entente against Bolshevism“,

or “negotiate with the Bolsheviks and in order to put pressure on the Entente to achieve an uncostly peace.”

Part of the military elite and major capitalist industrialists, whose benefits were severely infringed by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, supported cooperating with the Soviet state.

The Soviet Union, having reached an agreement with Germany on modernization of some Soviet defense enterprises, received the opportunity to create and test the latest developments, teach both military and civilian specialists, and work with the latest models of equipment produced by German technology. In return, Germany got access to the raw materials it needed, the opportunity to place defense orders in the USSR and improve German technologies.

However, part of the German elite still had a radically anti-Soviet mindset. There were some members of the military elite, such as Erich Ludendorff and Max Hoffmann, industrialists Fritz Thyssen, Albert Fögler, Karl Duisberg and Arnold Rechberg, banker Hjalmar Schacht, media mogul Alfred Hugenberg and publicist Paul Rohrbach. The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) became a powerful center of crystallization for this group. Created in 1919 as the German Workers’ Party by representatives of the Pan-German Union and renamed the NSDAP in 1920, it absorbed the most radical public figures. The imperial rhetoric and the urge to revise the terms of the Treaty of Versailles made this party desirable both for ideologues dreaming of empire, as well as for the industrialists and the military.

On September 1, 1939, Germany began World War II, defeating Poland and occupying its territory. By 1941, Germany had defeated France and conquered almost all Europe, and it was ready for a campaign on the east.

On April 2, 1941 Alfred Rosenberg, then head of the foreign policy department of the NSDAP and chief of the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, handed a report to Aldof Hitler, Germany’s Fuhrer. Report #1 proposed the division of Soviet territory into 7 districts. It conceptualized Russia as having a Russian historical center (Moscowia) and groups of annexed standalone regions it seized over the centuries, with populations differing from the Russian center in both the cultural and religious sense.

Rosenberg addresses Ukraine in his memo:

“Political goals in this territory might be the support for national identity, possibly to the degree of founding sovereign states, which could exercise the permanent containment of Moscow and provide security from the East for greater German living space, either as standalone or in cooperation with Don and Caucasus within The Black Sea Alliance.”

Hitler discouraged Rosenberg’s fascination with political games. The Fuhrer opposed the preservation of Ukraine as a standalone state. Five days later in his second report, Rosenberg used more ambiguous formulae: independent Ukrainian state “in a tight, unbreakable alliance with the German Reich.”

He wrote below: “After the collapse in 1918 the Ukrainian government made a proposition to the Wehrmacht Supreme Command to never return its stationed troops home, but to impose Ukrainian citizenship on the German soldiers and employ them against Moscow and Bolshevism. These formidable plans couldn’t rally enough political will at the moment”. Twenty years later Germany possessed enough of this “political will” to revive its march to the East.

An even harsher option for Ukraine exploitation – as part of the “Ost” plan – was developed on behalf of Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler by Konrad Meyer-Hetling, head of the planning department of the “SS Chief Staff of The Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood“. Meyer’s version deals with the creation of German settlement marks on the territory of Tavria (including the Dnepropetrovsk and Zaporozhye regions) and Crimea, as well as the “Germanization” of the occupied territories and the relocation of the native inhabitants to other areas.

It should be noted that today’s Ukrainian government operates in the southeast in the spirit of the Nazi “Ost” plan. The method of cleansing the territory of the “unwanted” population is shelling, which is used both to kill civilians and to “drive them off the land” (citizens who are still alive but frightened by the shelling begin to leave their homes). At the beginning of the so-called “Anti-Terrorist Operation” (ATO), specifically on July 14, 2014, the head of the Russian Federal Migration Service Konstantin Romodanovsky stated, “Since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine, about 130 thousand Ukrainian citizens have applied to the Russian authorities with a request to allow them to stay in the Russian Federation for an extended period of time.”

During World War II, one of the Reich’s main objectives was to force Ukraine to supply Germany with food (just as during World War I). Alfred Rosenberg stated on June 20, 1941:

“The provision of food for the German people during these years will be the most important German demand in the East, the southern regions and the North Caucasus will have to serve as compensation in food provisions for the German people. We do not at all consider ourselves obliged to also feed the Russian people at the expense of these fertile areas.”

Reichskommissar in Reichskommissariat Ukraine Erich Koch shared the same opinion. At a meeting in Rovno held on 26-28 August 1942, he stated:

“There is no free Ukraine. The purpose of our work is to make Ukrainians work for Germany, not to make these people happy. Ukraine must supply what Germany does not have. This work must be carried out without regard for losses… The shortage of grain must be filled at the expense of Ukraine… The Führer demanded 3 million tons of grain from Ukraine for the Reich, and it must be delivered. He does not want to hear complaints about a lack of vehicles.”

Reichsleiter Martin Bormann formulated the essence of the new ideology of Germany very clearly on July 23, 1942, in his letter to Rosenberg:

“…we must take the necessary prophylactic measures to prevent an increase in the non-German population. … Therefore, under no circumstance shall German health services be provided for the non-German population in the occupied non-Eastern territories. So, for example, under no circumstances shall immunizations and similar preventive medical services be so much as considered. The non-German population shall not be afforded any form of higher education whatsoever. If we were to make this mistake, we would in fact be planting seeds of future resistance. So, the Führer is of the opinion that it is more than sufficient that the non-German population – including the so-called Ukrainians – learn to read and to write.”

In order to substantiate the historical claims of Germany on Crimea, the history of the ancient Crimean Principality of Theodoro was used. According to historical data, the Principality was inhabited by members of ancient Germanic tribes – the Goths. In July, 1942, a special archaeological expedition to the Crimea was organized. Its organizer was General Commissar Alfred Frauenfeld, its direct supervisor was Ludolf von Alvensleben, the chief of the SS and police in Tavria, and lastly, the archaeologist – Werner Beumelburg. In the course of the expedition the ruins of the Mangup fortress – the capital of the principality, destroyed by the troops of the Turkish Sultan Mehmed II in 1475 – were inspected. The result of the expedition was the conclusion that the Mangup fortress is a typical example of Gothic fortification art.

In order to settle the Crimea with a German population, Frauenfeld recommended transplanting Germans from South Tyrol there. In his opinion, this would resolve the old Italian-German dispute over the territory. Henry Picker, who worked for many years as Hitler’s stenographer, and who in 1951 published a book with recordings of his conversations, which is currently banned in the Russian Federation, writes that Hitler approved of Frauenfeld’s idea. According to Picker, Hitler stated that it was a great idea, that the Crimea is both climatically and geographically ideal for the Tyrolese, and compared with their homeland it really is a land of milk and honey. And that their transfer to the Crimea would cause neither physical nor psychological difficulties. These and other similar plans were thwarted by the defeat of Germany in the war against the Soviet Union and its subsequent division into West and East.

The reunification of Germany in 1990 became a preface to the breakup of the USSR. The conditions of the new, post-Soviet era that followed dictate new forms of German interest in the fate of Eastern Europe and the post-Soviet space.

In 1992, Germany was one of the first countries to open an embassy in Ukraine. In 1994, Ukraine signed a Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with member states of the EU, among which Germany plays a leading role.

Germany succeeded in incorporating the countries of Eastern Europe, once part of the Soviet sphere of influence, into the EU. Thanks to its support, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania joined the EU in 2004. In 2009, Ukraine became part of the EU’s international project, the Eastern Partnership.

Today, after the maidan in Kiev, the tragedy in Odessa, and against the backdrop of the endless civil war in the Donbass region, there is no doubt remaining about what pro-Bandera Kiev sees as the essence of its proclaimed European course.

Obviously, the consequences of this Ukrainian course are an extreme degree of Russophobia, the opposition of the Ukrainian language to the Russian language, the severing of historical ties between the Russian and Ukrainian peoples, the nurturing of special forms of Ukrainian anti-Russian nationalism, covered up by the rhetoric of concern for the Ukrainian nation and the protection of Ukraine from Russia. All this is done under the auspices of Europe, in which Germany clearly plays a particularly important role. And using this role, Germany promotes its interests in Ukraine today with the same insistence as it did at the beginning of the 20th century.

The situation in Ukraine deteriorates at an exponential rate. The country faces both economic and political collapse and once this collapse happens it will inevitably damage the interests of the European Union, which has chosen to create such grievous ties with Ukraine. So, could it be that Germany once again will attempt to impose external management over Ukraine to avoid such a collapse and minimize it and its partner countries in the EU’s expenses, and how closely will these measures resemble those imposed by Germany early in the 20th century?

Source (for copy): https://eu.eot.su/2022/04/06/ukraine-in-germanys-plans-for-world-order-rearrangement-ukrainism-chapter-i/

This is the translation of the Chapter I of the multi-authored monograph “Ukrainism: Who constructed it and why” first published in 2017 and re-published on the Rossa Primavera News Agency‘s web-site on March 5, 2022. This research work was written by the members of Aleksandrovskoye commune, which is part of the School of Higher Meanings of the Essence of Time movement and is supported by the members of the Experimental Creative Centre International Public Foundation.

Dr. Sergey Kurginyan is a political and social leader of the Essence of Time movement, theater director, philosopher, political scientist, and head of the Experimental Creative Centre International Public Foundation.

Speaking about the topic of the monograph “Ukrainism: Who constructed it and why”, Sergey Kurginyan explained, “We are studying Ukrainism, not Ukraine. Our subject is Ukrainism as a construct. The creation of this construct, its characteristics, its consecutive transformation, its implementation, and finally its outlook―this is the focus of our study, which is thus fundamentally different from a normal historical or sociological study of a normal Ukraine”.