1

The tactics of the American Trotskyists are political vampirism. First, they offer a “more perfect” form for content that has already appeared without their participation and has its own energy, and then this form destroys the content.

History objectively indicates that the Communists managed to gain a foothold for a long time only in those countries where their ideas were consonant with the deepest aspirations of the people. This is confirmed by the victorious experience of the Red people’s liberation struggle from Cuba to Vietnam. And even more so, this was so in the acceptance of communism by Russia, communism as the eternal dream of the people about the good kingdom of justice.

Let’s try to trace the development of the left movement in the United States and its difference from others. But, starting to discuss this issue, it is necessary to at least give a general overview of the historical roots of the American Left.

It so happened that the resistance to the flagrant injustice of American society in the era of wild capitalism arose simultaneously in different ways, independently and separately. By the middle of the 19th century, four different movements were born in the United States that bore the makings of Red. But each of these movements, having closed itself off in its own separate group of interests, could not comprehend itself as sections of a united front even when some of their representatives began to argue in terms of the class struggle.

The four components of American leftism are:

- The populist movement of American farmers;

- The nascent trade union movement;

- Abolitionists, who evolved after the abolition of slavery to defending the rights of black people;

- The first wave of feminism in the form of the suffrage campaign for the right of women to vote.

The farming movement of populists, outraged by the increasing pressure of large financial capital on small farms, became a truly powerful political force by the 1890s. However, it soon turned out to be largely co-opted by the Democratic Party, which adopted its slogans. The sunset of this movement was partially described by Robert Penn Warren in the book All the King’s Men, and the main character of the book, Willy Stark, who represents this movement.

Unions and the strike movement began to develop in the US with the strengthening of industrial capital, after the end of the American Civil War. It was the trade union leaders, many of whom were initially attracted to anarcho-syndicalism (such as Eugene Debs and Bill Haywood), who later formed the backbone of the emerging Socialist Party, which was striving to give more organization and cohesion to the free-running strike movement.

The abolitionist movement and the black rights movement generated by it, built on the basis of the thesis of the unity of the human race, would seem to be a natural ally and an integral part of the Left movement. However, they had their own problems: white activists for a long time occupied the dominant role in the leadership of this movement, which caused scepticism among the blacks themselves, reminding them of other white “benefactors”, like supposedly progressive-minded plantation owners.

The first wave of feminism in the USA, as well as throughout the rest of the world, was tightly connected with the Left movement, but suffragists, although they participated in many socialist actions, nevertheless always presented themselves as a separate movement, which prevented them from agreeing on the priority of issues, solutions to which were obviously in the interests of both parties.

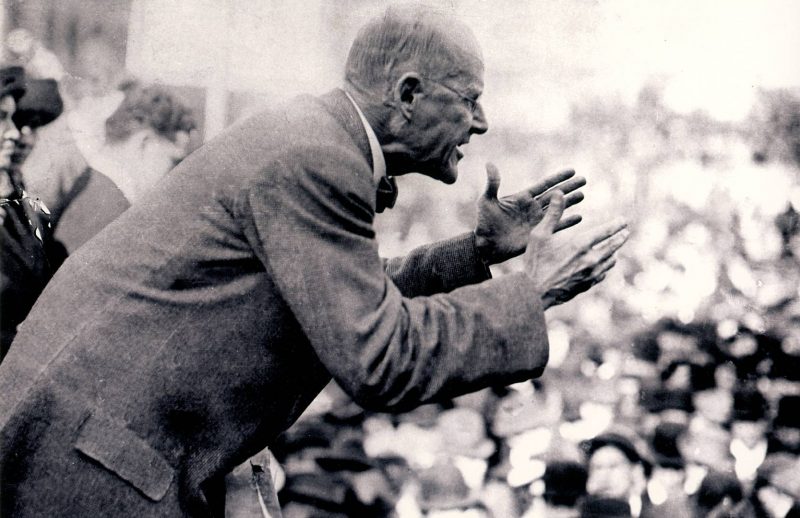

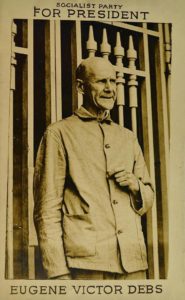

And yet, despite the fragmentation of the left movements, the new US Socialist Party at the beginning of the 20th century grew stronger and grew along with the strike movement. In 1904–1912 it began to play a prominent role in US politics. Its leader Eugene Debs, having gone beyond the limits of direct action tactics, attracted wide public attention to the party by his participation in the presidential elections. At the same time, such literary works as Jack London’s acute social dystopia The Iron Heel and the sociological novel by Upton Sinclair The Jungle exposed the inhumane exploitation, even to readers far from the working class.

Wanting to consolidate the conquered left bridgehead among the American intelligentsia and especially students, Upton Sinclair and Jack London together with other prominent scholars of the humanities formed the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. However, under the influence of the first “Red Scare” with widespread anti-socialist propaganda launched in the USA after the victory of the Great October Socialist Revolution in Russia, this organization changed its name to the League for Industrial Democracy and played a minor role on the political stage until the early 1960s.

The relative success of Eugene Debs in the presidential election of 1904 seriously worried the US government. This is also why the presidential administrations, first of Theodore Roosevelt, and then Woodrow Wilson, began to implement reforms introducing some restrictions on large businesses and implying certain obligations of the employer to workers, which can be seen to parallel European Fabianism. These reforms had an effect, creating a split in the Socialist Party – between revolutionary socialists and supporters of gradual reforms. At the same time, moderate reformists, although they occupied important positions in the party leadership, greatly lost in numbers.

When news came from Russia about the accomplished proletarian revolution, most revolutionary socialists took this news with great enthusiasm and expressed a desire to follow the example of the Bolsheviks. In response to this, the moderate leadership of the Socialist Party at the emergency congress of 1919 tried to deprive representatives of a number of primary organizations of the right to address the congress. This led to a temporary split in the left wing of the party. The majority, in which recent immigrants from Europe played an important role, left the Socialist Party and announced the creation of a new US Communist Party. The minority, led by journalist John Reid, who became widely known after the publication of his book Ten Days That Shook the World, tried to turn the tide in the Socialist Party, but it was defeated; and instead of joining the newly formed Communist Party, created its own alternative party.

Over the following months, the two competing structures bombarded the Comintern with requests to recognize themselves as the only legitimate Communist Party in the United States. Only after the Comintern ordered the two factions to end the quarrel and unite did the United Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) appear.

In its combined form, the US Communist Party lasted until May 1929, when supporters of L. D. Trotsky officially announced the creation of their own Communist League of America (CLA). The leading role among the Trotskyists was taken by James Cannon, who had previously been in Moscow on the affairs of the Comintern and was personally acquainted with a number of key figures in the senior leadership of the Bolshevik party. After reading Trotsky’s 1928 article “The draft program of the Communist International. Criticism of the Foundations,” Cannon completely sided with Trotsky. Returning to the United States, he began to defend the position of the Trotskyists, and was soon expelled from the Communist Party, taking away part of the key activists with him.

The newly created party of the Trotskyists, united with a number of small left-wing structures with roots in the trade union movement, changed its name several times, and for a short period of time in 1936–37, it ostensibly disbanded and joined the Socialist Party as a whole with the goal of radicalizing it. After being expelled from the Socialist Party, the Cannon group adopted the name under which this organization exists to this day – the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

As Trotskyists, the members of the SWP, led by Cannon, held the view that in the Soviet Union there was a “degenerated workers state” in which the bureaucracy replaced the Soviets. Formally, the SWP members adhered to pro-Soviet rhetoric; however, the entire price of this rhetoric became apparent during the Great Patriotic War and the United States entering World War II in December 1941. Through the mouth of their leader, the American Trotskyists declared that the Second World War was imperialist and that there was no difference between the United States, which entered the war on the side of the USSR, and Nazi Germany – as they were both imperialist states (does this rhetoric remind you of anyone?). Consequently, Cannon said, American workers should evade conscription and intensify strikes, especially at defense enterprises.

James Cannon acted as the first person and the main speaker of the party, around whom his own minor cult of personality began to take shape, but until the outbreak of World War II, Max Shachtman was the main party ideologist, who, like Cannon, became a Trotskyist and was also expelled from the Communist Party in October 1928. A split between Cannon and Shachtman occurred before the war due to their assessments of the role and value of the USSR. Unlike the Trotskyists’ dubious, but not radical position of the “degenerated workers state”, Max Shachtman and his followers proclaimed that the Soviet Union was no “workers state”, but an example of “bureaucratic collectivism” with a new ruling class. Consequently, Shachtman concluded, the labor movement should strive for an early defeat of the USSR, which should then open up new opportunities for the global class struggle. It is noteworthy that after some time the widow of Trotsky, N.I. Sedova also adopted Shachtman’s position.

Later, students and associates of Max Shachtman brought his thought to its logical conclusion and began to implement it. A prominent of Shachtman, but by no means his only ally, was James Burnham, a professor at New York University, who had previously held a key role in the leadership of the SWP and left the party with Shachtman. With the entry of the United States into the war, Burnham, at the invitation of diplomat George Kennan, was tapped to head the department of political and psychological warfare in the newly created Office of Strategic Services (OSS, the predecessor to the CIA). With the end of the war, Burnham turned sharply to the right, and together with the writer William Buckley, founded the magazine The National Review.

The goal of the magazine, according to Buckley, was to “support the most right-wing, viable candidate” in any election. In 1964, the magazine helped Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater, who called for the use of nuclear weapons in Vietnam, become the Republican candidate in the presidential election, who he then lost to Lyndon Johnson. And in 1980, with the active support of Burnham and Buckley, Ronald Reagan was nominated, and then won the election. Ronald Reagan, who abandoned the Nixon policy of “detente” and greatly aggravated the confrontation with the USSR. An important support group for Reagan was a team from the Nixon administration, which had previously tried to marginalize Henry Kissinger as the chief architect of detente, and which later became known as the neocons.

But back to Cannon’s party. Before and during the war, they adhered to the tactics of entrism, that is, the tactics of joining existing movements in order to implement projects with them that are relevant for both sides, as they lead to some common, albeit intermediate, goal. The seizure of intellectual dominance in trade unions and the movement for black rights led either to the radicalization of their actions or to the SWP absorbing breakaway elements.

However, with the end of World War II, the positions of the left in general and the Trotskyists in particular in the USA began to rapidly weaken. This was the result of a sharp increase in living standards, a patriotic upsurge, and the “witch hunt” that Truman initiated and was continued by Eisenhower who replaced him. That famous surge of anti-communism is firmly connected in history with the names of Senator Joseph McCarthy and FBI Director John Edgar Hoover. For the Trotskyists, who did not leave for right-wing anti-communism along with Burnham, the time came to hold out and wait.

Everything changed in the early 1960s. On the one hand, the victorious Cuban revolution generated a new wave of optimism, giving hope to a whole generation of American students for the possibility of a socialist revolution in the near future. On the other hand, the increasing involvement of the United States in the counter-guerrilla war in Vietnam fueled both general anti-imperialist sentiments and a very specific outrage that poor people were the ones being sent to die in the foreign jungles of Vietnam.

The student section of the League for Industrial Democracy, already mentioned by us, founded by Upton Sinclair and Jack London, managed to harness these moods to the fullest extent. The student branch changed its name to another – Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and became the core of the New Left movement’s growing strength. Established in 1962, this organization declared the principle of direct participatory democracy as its central principle, which resulted in massive student anti-war demonstrations throughout the country. However, the lack of a centralized leadership and a tendency to be distracted from its main activity by sexual excesses and drugs led to splits in the organization and its seizure by external forces, including members of the youth branch of the SWP – the Young Socialist Alliance (YSA), who infiltrated its ranks.

By 1969, the SDS as a single organization ceased to exist, splitting into many dwarf groups. The organizational and media resources of the SDS came in the hands of a strange organization called The Weathermen. This name was taken from Bob Dylan’s song “You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows”.

Faced with the ineffectiveness of peaceful anti-war protests, the Weathermen first tried to organize massive violent anti-war demonstrations in Chicago. But when it turned out that they did not have a large group of followers, they switched to the tactics of so-called urban guerillas, mainly practicing the laying of improvised explosive devices inside government institutions, including the Pentagon and the Capitol, as well as a number of less significant objects. The domestic terror attacks were accompanied by printed proclamations, the general meaning of which was that the Weathermen were engaged in “bringing the war back home” – in fact, it was a perverted version of Lenin’s – “to turn the imperialist war into a civil war.”

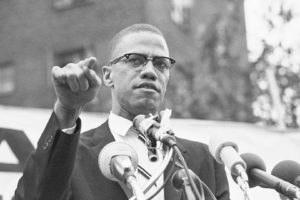

The Weathermen declared themselves allies of the Black Panther Party, created in 1966 amid the indignation over police brutality against black people and largely guided by the teachings of Malcolm X. Malcolm X contrasted himself with the mainstream black civil rights struggle, personified by Martin Luther King. King sought to maximize the integration of black people into American society, but Malcolm X, on the contrary, called for extreme isolation including armed action against law enforcement and for separatism.

Unlike the defiantly public Black Panthers, the Weathermen were underground and adhered to strict secrecy. While the FBI and the police managed to arrest or liquidate many of the most prominent leaders of the Black Panther Party, the Weathermen generally avoided a similar fate. With the defeat of the United States in the Vietnam War, the Weathermen lost the main motivation for their activity, which gradually diminished and ended with the dissolution of the organization in 1977.

In 1971, the FBI’s program COINTELPRO (Counterintelligence Program) for monitoring and infiltrating FBI and CIA officers into the ranks of the Black Panthers and Weathermen, allegedly personally led by FBI director John Edgar Hoover, was exposed the American press. The source of these materials is believed to have come from Citizens’ Committee to investigate the FBI, whose members remain unknown to this day. According to the story, activists of this committee entered the building of the FBI Office in Philadelphia at night and stole secret documents on the surveillance and infiltration program. The publication of these materials in American newspapers caused a major scandal and severely spoiled the position of the state prosecution since it turned out that most of the evidence against the Black Panthers and Weathermen was obtained illegally. This led to the effective amnesty of many members of these organizations, although some of them were later successfully prosecuted for minor criminal offenses or misdemeanors.

The story of COINTELPRO’s revelation is striking in its dubiousness – after all, according to the official version, some “unknown activists” managed to get into the FBI Office of a major city and found exactly those documents that contained details on a top secret surveillance and infiltration program! One cannot help but wonder: was this not an orchestrated leak in order to cover up the true nature of the relationship between the US security services and the organizations that they were allegedly “investigating”?

In order to return this strangeness to its historical context, it should be recalled that at about the same time, paramilitary leftist structures (such as the Red Brigades in Italy and the Red Army Factions in the Federal Republic of Germany) were operating in several European countries, using similar tactics to the “Weathermen”. An independent investigation into the activities of these structures in Europe revealed a direct link between the intelligence agencies of NATO countries and these militant groups through the Gladio network. Given the similarities in tactics between the European and American leftist terrorist groups, as well as the serious dubiousness regarding everything related to COINTELPRO, we consider it appropriate to put forward the hypothesis that the Gladio network operated on the territory of the USA itself.

Having been set free or having completely avoided persecution, the Weathermen and Black Panthers did not disappear into non-existence, but began to build their future lives in different ways. A number of Weathermen, along with their more moderate counterparts in the SDS, went to universities, where many still occupy professorial appointments in the humanities. Others came either to the Socialist Workers Party already familiar to us, or to one of the many leftist groups that had split from the SDS. Among these groups, it is worth highlighting the American (not to be confused with the German) “Spartacist League”, created by the followers of Max Shachtman and managed to transiently be a part of both the SDS and the youth division of the SWP. Its activity is noteworthy in that in the early 80s, together with other fragments of SDO and SWP, they actively supported the Polish “Solidarity”.

The Black Panther Party during the 1970–80s. began to actively criminalize, including providing security for drug dealers and gradually falling apart into separate street gangs, formally warring with each other. The charismatic leader of the Black Panthers, Huey Newton, was himself killed in 1989 during a meeting with a drug dealer in Oakland, California. The two largest associations of street gangs breaking away from the Black Panthers, the Crips and the Bloods, continue to control a significant share of the intra-American drug trade.

Recently, fragments of the SDS began to gradually gather again around a party called the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). Having experienced explosive growth after the election of Donald Trump as the US President, the DSA seeks to actively participate in the affairs of the Democratic Party, influencing both its policy through the active promotion of identity politics, and directly by promoting its activists as candidates from the Democratic Party for local and federal elected posts. Among the most prominent politicians associated with the DSA are Vermont Senator Bernard Sanders, who is participating in the democratic primaries of the presidential election, and Alexandra Ocasio Cortez, recently elected to the House of Representatives from the State of New York.

In conclusion, we note that studying the history of the Trotskyist movement in the United States suggests that the tactics of the Trotskyists in the United States are more than just entrism. The tactics of the American Trotskyists are political vampirism.

In a movement that arose without their participation, and which gathered great energy, the Trotskyists enter as a virus. Then they either direct this energy according to their goals, which helps them build up political capital (it is presented as an aid in “mastering the right Marxism”, in theoretical education, in propaganda through well-established organizational schemes), while simultaneously leading to the radicalization of the movement. If, however, efforts to seize control of the movement fail, a split is provoked and some of the fragments are absorbed; that is, at first the Trotskyists offer, as it were, a more perfect form for a content that has already appeared without their participation and has its own energy, and then this form destroys the content.

It was this tactic of political vampirism that caused serious damage to the once powerful American trade union movement. Because of it, the promising antiwar movement of the 1960s and 70s discredited itself in the eyes of the general public. The political vampirism of the Trotskyists severely damaged the black rights movement, sending it on a destructive course of the armed confrontation. Along the way, the class struggle so beloved by the Trotskyists was replaced by a “racial” struggle.

Today it is clear that American leftists intend to continue to apply vampire tactics in relation to a wide range of “oppressed groups” that are transformed by identity politics into disparate political interest groups. Against the backdrop of the 2020 presidential campaign approaching the United States, it is clear how the exploitation of the theme of small groups being “oppressed” on the grounds of race, gender, sexual orientation, etc., becomes the mainstream of the rhetoric of the US Democratic Party, which has long (falsely) positioned itself as “the party of the working man. ”

A separate serious examination is required for the phenomenon of the mass transition of the Trotskyists and especially the followers of Max Shachtman to right-wing anti-communism and the emergence of the neoconservatives on their foundation. A more detailed study of the nature of the relationship between American Trotskyists and the US security services at different stages of their history is also necessary. All this is especially relevant for today’s Russia, given the active planting of “Marxist” discussion clubs with clearly Trotskyist content and specifically Trotskyist leftism suddenly becoming en vogue.

Source (for copy): https://eu.eot.su/2019/08/29/trotskyism-in-the-usa-or-the-age-of-political-vampirism/

This is the translation of an article by Lev Korovin, first published in the Essence of Time newspaper issue 338 on July 27, 2019