1

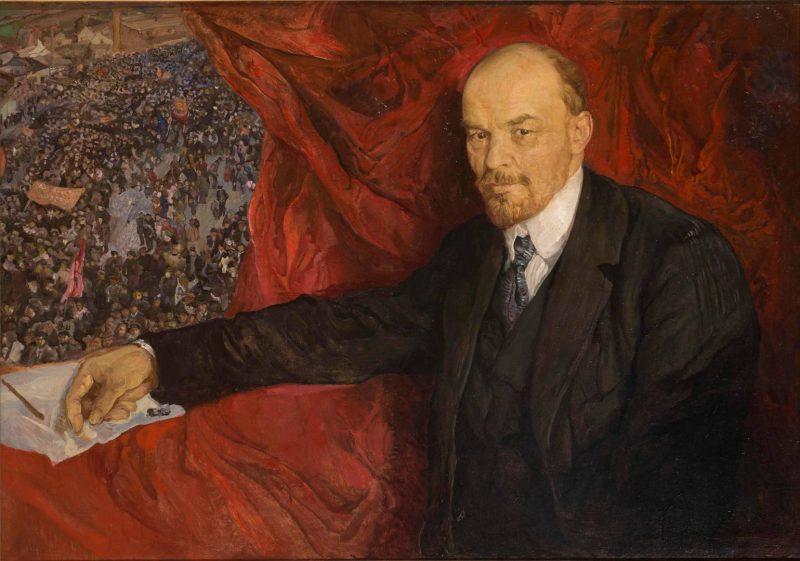

To Vladimir Ilyich Lenin’s 150th Anniversary

We celebrate the 150th anniversary of the birth of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin in a very peculiar situation. To reduce it to the global shock of the coronavirus is to significantly oversimplify the essence of the matter.

But ignoring this shock would also be strange. Because more and more people are beginning to understand the mismatch between the scale of the coronavirus disaster and the global response that this disaster has caused. This mismatch is usually referred to as a “scissors”. In the case of coronavirus, we can talk about the “2020 scissors”.

And it’s far from pointless to compare these scissors to others. Because the presence of such “scissors”, which represent a blatant over-reaction to certain, albeit very sad, events, always indicates the artificial nature of these reactions, and perhaps of those events, to which they are reacting so excessively.

The degree of excess reaction is sometimes called the breadth of the scissors. The coronavirus shock has shown us all that the scissors can open to a much more impressive extent than people thought, as they are justifiedly spellbound by the flow of global consumerist life, which seemed to promise us nothing extravagant. Glorifying the established order of things, the philistine was convinced that life today is the delight of the consumerist existence, in which everyone is concerned with the brand of cars purchased and the convenience of the parking spots, which should be provided to their owners. And the life of tomorrow is… It is an even greater delight in the same type of existence.

And now, for some unknown reason, this glorious life was curtailed overnight! It was curtailed without even saying anything about what caused such a furious curtailment, or when it would end. And also, what will be found on the other side of some obscure and unconvincing end to what happened. Then it is time to talk about the wide open “scissors.” In other words, a sort of shadowy, multi-level lack of clarity. And to discuss each of its levels.

Level 1 – The very nature of what happened is unclear.

Are we dealing with a biological war, being waged by whom? China? The United States? Someone else?

Are we dealing with an unprecedented natural disaster? But then why is it unprecedented, what does it mean, why has it become possible now? How long will it last? How unique is it? How should we react to it?

Or are we dealing with plotting by some massive non-state or supranational forces… Which ones? The deep state? Large multinational pharmaceutical companies? Forces that aim to rearrange the world, that are crawling out of the deep underground?

Level 2 – The unclear reaction to an unclear disaster.

If the disaster threatens the existence of all humanity and individual nations, then why do the statistics show otherwise? Where is the deadly certainty of the disaster that can even somehow unite people? Or that can at least prevent the global and regional misunderstanding about what precisely is happening from boiling over?

Level 3 – The depth and content of the so called “reactive pause” is unclear. So a certain disaster has occurred. So it caused a paralysis of public life. What’s next? Is it forever? Is this for a couple of months? Is it going to last some short time and then reappear after another brief interval? Or will it never happen again, and we’ll go back to how things were before? If we don’t return there, then what will we return to and when?

Level 4 – The meaning of what is happening is unclear. Is this misfortune a punishment for certain sins? Which sins? Have we encroached upon nature, and she is taking revenge? What should we do in this case? Bow down before her omnipotence and make a sacrifice on the altar of Mother Nature? What sacrifice?

Is what has happened the evidence of nature’s insurmountable omnipotence? Then what comes of this omnipotence? It’s really like something out of Hamlet:

To be, or not to be, that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take Arms against a Sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them…

What taking up of arms can we talk about?

What can this taking up of arms look like?

Will Man stop being part of nature?

Will humanity separate itself from nature by insurmountable barriers, contraposing virtuous artificiality against evil naturality, ceasing to eat not only bats, but any organic food, starting instead to eat synthetic food? Shall it also start collecting artificial plastic berries and mushrooms in artificial plastic forests, which are guaranteed to be sterile?

What will people turn into after they begin to submit to nature and agree to the consequent sacrifices (“let so many die, but the others will continue to live the same way”), or resist the fury of nature of unknown origin (“put on isolation suits, invent medications, etc.”)?

Is a response to what happened possible in the form of a set of far-reaching projects? The ones that I described or others?

What will these projects entail?

What consequences will they have for different nations and different social groups within the same nation?

I risk making two historical analogies here, which are quite obvious to me, but are unlikely to be obvious for others. While both analogies have a direct bearing on the figure of Lenin and on the anniversary that we are now strangely celebrating.

One of these analogies is with the beginning of World War I. There were strange “scissors” then, too. A terrorist named Gavrilo Princip killed Archduke Ferdinand of Austria for some reason and with someone else’s help. One would think, “So what?” Yes, a tragic event took place that requires some kind of reaction. But it couldn’t have occurred to anyone that the death of this rather bland figure could lead to a global disaster on an unheard-of scale. Furthermore, the declared sanity of the bourgeois order, created according to the recipes of the Enlightenment, made such madness impossible.

And everyone started to ask themselves what the “1914 scissors” signify, i.e. the huge gap between the scale of the disaster (murder of one person who was not even a head of state) and the scale of the reaction (world war). Are the British plotting? Have the Freemasons begun to reshape the world? Have the Jews decided to force the establishment of the state of Israel? Are German occultists arranging a global gathering of the witches? Do the arms dealer Basil Zaharoff and Vickers want to sell more weapons? Is someone unhappy with the Berlin-Baghdad railroad?

And most importantly, once the madness has started, what’s the way out of it? Everything can’t just happen according to the principle of “we killed some people, calmed down, and returned to business as usual.”

The “1914 scissors” stirred the minds of contemporaries who wondered about the cause and consequences of what happened. At the same time there was one and the same problem within these speculations, sometimes rather deep, and sometimes superficial and hysterically stupid. The speculators could end up guessing something. But they couldn’t change anything.

The only one who combined guesswork and action was Lenin.

In his brilliant work Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, Lenin explained exactly the nature of the “scissors” between the murder of an Archduke and the global disaster.

Lenin insisted that the reason was the uneven development of the leading states in the imperialist era.

Lenin outlined the contours of this era, contrasted its sinister novelty with what was inherited from classical capitalism.

Lenin described what is happening within this nature of this new capitalism, which is called imperialism.

Lenin was the first to reveal the accumulation of new contradictions stemming from the nature of this new capitalism, i.e. imperialism. And he proved that the accumulation of these new contradictions can consequently only lead to world wars.

And finally, Lenin revealed Russia’s role as a weak link in the chain of new states, which were no longer just capitalist, but imperialist.

In doing all this, Lenin undoubtedly demonstrated his genius as a political analyst, political philosopher, political futurologist and so on. It is certainly possible to call Lenin a genius scholar for this reason. But this is just as wrong as calling Marx such a scholar.

Neither Marx nor Lenin were scholars in the strict sense of the word. They were prophets, visionaries, and pathfinders. It’s a different thing entirely that for a long time, Lenin justifiably considered Marx alone to be such a pathfinder, predictor, prophet, and sage.

And only in the situation of the”scissors” did Lenin take on the role of discovering the nature of what was happening, which Marx had played during the previous period. All the while, Lenin did not belittle Marx’s role, let alone advertise his role.

The further Lenin left Marx in essence, and this could not but occur in the conditions of the shocking novelty that the 20th century revealed to humanity, the more insistently Lenin spoke about how unsurpassed Marx was and how he was Marx’s disciple.

This was both Lenin’s organic modesty and his pragmatism. Lenin understood that once he spoke of himself as a new prophet, the fermentation of minds would begin, and many of his contemporaries would want to play the same role. The fermentation of minds would also turn into political fermentation, and thus would hinder the main task – the task of responding to the challenge posed by the “1914 scissors”.

It was important for Lenin not only to reveal the nature of these “scissors”, but also to give an answer to the challenge that arose from the revealed nature of the “scissors”. It is difficult for me to point out that there is something similar to this double genius of Lenin’s in world history: the genius of understanding and the genius of overcoming the understood.

Meanwhile, a close acquaintance with the period from the beginning of World War I to the Great October Socialist Revolution leaves no doubt that it was Lenin who personally, having understood the nature of the global “scissors”, overcame what this nature, i.e. imperialism, promised a stunned humanity, if not forever then for many years.

Of course, Lenin did this, relying on a certain (incidentally, not very wide) circle of loyal and talented comrades.

Of course, he understood the correctness of the words spoken by Alexander Blok about the the modern hero’s lack of freedom, “The hero free strikes no longer – His hand is in the people’s hand.” Lenin was very acutely aware of this lack of freedom for the striking hand, which is also a close dependence on the people’s support and the people’s willingness to make sacrifices on the altar of the new fair state and public life that the Bolsheviks promised.

Lenin was just as acutely aware of his dependence on that very “party of a new type” to which he had devoted himself entirely, without leaving a trace. At the beginning of its historical journey, this party accomplished great acts. And at the end of its historical path, it suffered a fiasco, unheard of in its humiliation.

Is it possible to examine the beginning while ignoring the end or the end while ignoring the beginning? Of course not. The party that Lenin brought up, which came to power under his leadership, called itself the party of Leninists until its end. But was it ever such a party? Lenin was still alive when the party betrayed him, refusing to consider the proposals of its leader, whose imminent death was all too obvious.

Of note, Stalin was never Lenin’s antipode. The myth of Stalin as a hidden White Guard, who corrected the Bolshevik anti-Russian excesses, never really convinced anyone, including the myth’s authors. It was too clear that Stalin really worshiped Lenin and considered himself the continuer of his cause. But the party’s insulting refusal to at least take into account its dying leader’s thoughts, for Lenin’s thoughts about the reorganization of the Rabkrin [the Worker’s and Peasants Inspectorate, which Lenin had proposed to transform into an “Inner Party” that would oversee the Party – translator’s note] can not be attributed to the sequela of brain disease, was something Stalin experienced very harshly. And he made the appropriate conclusions from this, according to which the party can be praised and “smothered in hugs”, but it cannot truly be trusted and relied upon.

So, Lenin constantly cared about both the party’s connection with the people and the state of the party as the country’s administrative and political management body.

Lenin understood the importance of popular support and party unity. He took very hard the party schisms and the party transformations that had obviously taken place in the era of the New Economic Policy (NEP), and which was fraught with separating the party from the people, which he took even harder.

But at the same time, both during the pre-revolutionary period and during the Civil War, and during the NEP period, Lenin acted mainly in accordance with his personal feelings, thoughts and volitional impulses. The paradoxicality of his personal decisions – this and only this allowed Lenin’s supporters to win power, defeat the White Guards, repel the Entente’s attacks, escape international isolation, and stay in power during the NEP period.

The February Revolution caused deep confusion in the Bolshevik leadership. It is easy to see that the only true assessment of what was happening was given by Lenin, who recently returned from years of emigration. And all those who were more connected to the Russian reality demonstrated such political inadequacy that would have turned into a fantastic Bolshevik fiasco in the absence of Lenin’s assessments and instructions.

The same applies to the Brest-Litovsk peace, the main decisions of the Civil War era, the transition to the NEP, and preventing this risky step from turning into a restoration of capitalism.

But even more so it concerns Lenin’s assessment of the “1914 scissors”.

There are different views on whether the renowned Zimmerwald Conference (the international socialist conference held in the Swiss village of Zimmerwald from 5 to 8 September 1915, which proclaimed anathema to the world war and recognized that this war is the eve of socialist revolution) was a demonstration of Bolshevik political sobriety.

Yes, Mayakovsky gave the Zimmerwald Conference exactly that assessment. Having initially described the unprecedented despair that the defeat of the 1905 revolution created, and the fact that Lenin, overcoming this despair, “turns exile into college, educating us for the coming battle,” Mayakovsky further sparingly draws the prospects of this process of Lenin resurrecting the defeated party (“Teaching others, himself gaining knowledge, regathering the Party, unmanned and scattered“). And then quickly moves on to the insane convulsions called World War I, which Lenin predicted, and without the logical occurrence of which, there would not have been the Bolsheviks’ victory, or the Soviet state, or the banner over the Reichstag in 1945. Many things would not have happened without this mad convulsion with its “1914 scissors”. But that’s just it, Lenin predicted this convulsion.

Of course, it was not some mathematically flawless prediction, which in history is not at all possible. The accuracy of historical prediction always has limitations, determined by both random circumstances and the very irreplaceable factor of the freedom of the human will.

But the historical will, absorbing the human will, acquires a substantially, though not entirely, deterministic character. That is the thing that this character cannot be considered entirely deterministic, completely deterministic, absolutely deterministic. This is why Lenin did not fully trust himself and his deterministic approaches. But at the same time, he managed to use these approaches in order to understand the nature of the “1914 scissors”. And when he did this, he was fully equipped to face new challenges.

I remind the reader that the economic work of Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism was written in Zurich in the spring of 1916 and published in Petrograd only in April 1917. So there can be talk of Lenin’s precocious conclusions – that smoke appeared, and immediately the leader of the world proletariat came to the necessary understanding of the historical process. I repeat, Lenin went through great suffering to get to the truth, he doubted his intuitive insights, he hesitated, sometimes he even despaired, saying that his generation will not live to see the revolution in Russia. And yet Lenin was able to find within the madness of the time that, which allowed him to act unmistakably in that most difficult post-February catastrophic situation.

Moving from describing the despair caused by the collapse of the first Russian revolution and the painful overcoming of that despair before 1914 to the events of 1914, Mayakovsky describes what I call the “1914 scissors” in his poem:

But then

came a year

that put off the fire —

1914

with its deluge of pain.

It’s thrilling

when veterans

twirl their whiskers

and, smirking,

spin yarns

about old campaigns.

But this wholesale,

world-wide

auction of mincemeat —

with what Poltava

or Plevna

will it compare?

Imperialism

in all

his filth and mud,

false teeth bared,

growling and grunting,

quite at home

in the gurgling ocean of blood,

went swallowing up

country after country.

Around him,

cozy,

social-patriots and sycophants.

raising heavenwards

the hands

that betray,

scream like monkeys

till everyone’s sick of it:

‘Worker —

fight on —

on with the fray!’

The world’s

iron scrap-heap

kept piling

and piling,

mixed with minced man’s-flesh

and splintered bone.

In the midst

of all this

lunatic asylum

Zimmerwald

stood sober alone.

Our pseudo-leftists are very fond of appealing to Zimmerwald’s antipatriotic stance, turning the accuracy of Lenin’s behavior at the time, generated by the unheard of madness of the era, into a general recommendation that communists should always strive to turn international wars into civil wars. And the “rightists” uncritically taking the pseudo-leftists bluffs, condemn Lenin’s antipatriotism, invented by the pseudo-leftists.

In fact, neither Lenin, nor the Bolsheviks as a whole, nor Marx had ever addopted an antipatriotic class position in its defeatist variant. For example, Lenin and the Bolsheviks did not call for the defeat of Tsarist Russia in the war with Japan. They reacted to this defeat, but that is all.

And the revolutionaries, who are considered the forerunners of the Bolsheviks, did not call for Turkey’s victory over Russia in the Balkan wars. For the most part, everything happened in a diametrically opposite way. But for the most part doesn’t always mean always.

Once in history, having guessed everything at once: both the essence of the situation and the consequences produced by the “1914 scissors”, Lenin made a painful, tragic decision. Which, I repeat once again, was in no way antipatriotic. For it was not about the necessity of Germany’s victory over Russia, but about the necessity to simultaneously depose of all the elites that unleashed the global madness, i.e. the “1914 scissors”. I emphasize: all the elites at once – Russian, German, English, and French. And so on.

The Bolsheviks never took the traitorous approach attributed to them by their detractors, according to which the defeat of the country in which they want to accomplish a revolution makes it easier for them to reach the desired revolutionary changes. Among other things, the Bolsheviks admired the patriotism of the French Jacobins, and discussed with bitterness the experience of the Paris Commune, which convincingly demonstrated how exactly the victory of a foreign country over your own (for the Commune of Paris – Prussia over France) does not result in the success of a revolution, but in its suppression.

Knowing this, discussing it many times from different angles, the Bolsheviks, in principle, could not say what the current pseudoleftists are screaming about, “Let our bourgeois state be defeated by another bourgeois state, and we will get great opportunities in elections in our country due to such a victory of another bourgeois state. For the people will lose confidence in the authorities, who lost the war.”

The Bolsheviks understood that if their bourgeois state was defeated, the victorious bourgeois state would deal first of all with the revolutionary forces in the defeated state, and this would give nothing to the defeated forces.

Lenin caught wind not of the possibility of profiting from the defeat of his own country, but something else. And having caught (as well as theoretically described) this, he laid the basis for his understanding of both the prospects of the February revolution and the possibility of the socialist revolution’s victory in Russia, and the special path of socialist Russia. Lenin felt the exhaustion of the entire existing world order. He understood that either a fundamentally new world order would emerge, or this exhaustion would turn into a full-fledged global civilizational catastrophe, in the abyss of which the bourgeois Russia, the bourgeois Germany, the bourgeois France, and the bourgeois England would perish. And not only the bourgeoisie will perish – as not only the patricians perished in the collapse of the ancient Roman civilization.

This is the greatness of Lenin as a true Russian patriot. This is the everlasting greatness of true revolutionaries, focused simultaneously on building a new life in their country and on the greatness of their country. Lenin was such a patriot. But he wasn’t the only one.

With a clarity and depth of thought, incredible for his time and almost unprecedented in historical terms, Lenin was both a man of action and a man of dreams. In other words, he was a man eager to realize his dreams, not an empty dreamer.

Seeing the essence of what was happening, Lenin did not intend to limit himself to such a vision: he wanted to use this vision to realize his dream of a new Russia. Lenin dreamed with a furious passion about this new Russia, great in its unheard of novelty, knowing how to make his furious dream come true. And I don’t know of any other great thinkers (“thinkers”, “prophets”, “political clairvoyants”) who would be endowed with a political effectiveness similar to Lenin’s. And this effectiveness was born out of an unprecedentedly passionate dream of a new path that Russia would show the world.

People could say: well what did it all result in?

I’ll answer. It resulted in both the grand achievements at the beginning of what is rightly called the newest history of humanity, and the grand disgrace at the end of this newest history, the transformation of which we are witnessing either into second edition of the “1914 scissors” or something worse – the beginning of the posthistoric dictate of forces hostile to humanity, which now have not only an imperialist and post-capitalist character, but also a fully post-imperialist character. But this makes it even more sinister.

For I said at the beginning that there are two parallels to the current “2020 scissors” that are relevant to Lenin. One of them I have already described. And the other is the disgraceful perestroika with its anti-Leninism, composed in the depths of the ruling party, which swore by the name of Lenin until its disgraceful self-destruction in 1991.

Now some non-transparent nomenklatura, no longer within the Soviet Union, but worldwide, which is dissatisfied with its project (the globalist, consumerist, information-consumer, etc. project), just as the Soviet nomenklatura was dissatisfied with the Soviet project, is organizing the dismantlement of its own project. It inflates the coronavirus myth in the same way as our nomenklatura inflated the myth about the horrors of Sovietism, Communism, Leninism, Stalinism, and so on.

The “2020 scissors” is strikingly similar not only to the “1914 scissors”, but also the “1985 scissors” or the “1991 scissors”. The mismatch then was striking between the real problems of the society that was being destroyed and the bubble that was being inflated in the form of savoring the Soviet situation’s deadlock and Sovietism’s endless crimes.

Now the discrepancy is striking between the bubble that is inflated over the coronavirus and the coronavirus itself.

Starting to discuss the essence of time in the epnymous project, which consisted of a series of video lectures, I warned that the global consumerist filth will not last long. That it was too unstable to last long. And that there’s no need for it to last that long. For it was only invented to crush the Soviet Union and Soviet communism. Only for this purpose, the ruling class temporarily began to feed and even over-fed its own population. Of course, not to the extent that Western propagandists described it, but still.

There’s no need for that now. And the feeding continues because it’s hard to cancel. They’re used to it. But it can’t be continued within the limits of the existing elitist social order, based on the blatant gap between the possibilities of the contemporary patricians and the possibilities of the contemporary plebeians, who long for the contemporary analogue of bread and circuses.

The law of competition has yet to be repealed. And it is unclear how to repeal it without a world war. And within the framework of this law, it is also impossible to pay so much to plebeians in the West, decomposing them, indulging their whims, wearing them out in the bosom of a peculiar comfort, brought about by the need to counteract the Soviet way of life this comfort. But this comfort can only be reversed together with the world order. Is this not a direct analogy to our perestroika?

150 years have passed since Vladimir Ilyich Lenin was born. He still lies in the Mausoleum. But his case has been trampled upon and insulted. And the experience of political Leninism – the discovery of the “scissors”, revealing their nature, the consequent prediction, the strong-willed dream of a new Russian messianism – has been thrown away as something unnecessary.

Such a casting aside of the essence of Leninism, along with the figurative and capricious encouragement of certain parodies of Leninism by our retro-communists and pseudo-leftists, promises very gloomy prospects for us all. It is time to return to the forgotten and insulted essence of Leninism.

But you can’t go back to it without redeeming the party, which at the end of its existence continued to whine about Leninism (the Brezhnev-era song “What are you dreaming about, the cruiser Aurora?”), and the people who were enticed by the pleasures of consumerism, which will now begin to be taken away on a global scale.

Having lost everything that was won by our ancestors as a result of the regress brought about through perestroika and post-perestroika, our people still have not formulated their attitude, firstly, to what exactly they have lost, and secondly, to the fact that without their decisive participation everything that was won could not have been lost.

Accordingly, the greater the scale of the loss, the greater the significance of what has been lost, the greater the responsibility of the people for that loss. Of course, I would like to detach one from the other, which Zyuganov’s Communist Party has been doing for decades, claiming that the people are not guilty of the loss of the Soviet state and the Soviet way of life. That it was not the people who threw it away for nothing, spitting on the great sacrifices made on the altar of the acquisition of these benefits, and thus trading the communist birthright for lentil pottage in the form of…

In the form of what?

Every year, people understand less and less what kind of lentil pottage there is to speak of. In exchange for what were the gains of Soviet socialism given up? Why did we have to throw away the communist prospects?

The people’s confusion is growing despite the fact that the situation requires the opposite. Either this demand will be heard and the confusion will be overcome, or this confusion will throw the people into the abyss of final historical exhaustion.

That is what I believe we should be thinking about as we celebrate this strange anniversary of Lenin.

Source (for copy): https://eu.eot.su/2020/04/26/the-essence-of-leninism/

This is the translation of an article by Sergey Kurginyan, first published in the Essence of Time newspaper issue 374 on April 24, 2020.